Written by Zenobia Morrill / Mad in America

Dr. Eric Greene’s new paper uses three cases to illustrate the systemic violence perpetuated by a mental health clinic in the US.

A recent paper, by Dr. Eric Greene, builds upon critiques of the biomedical model and illustrates how the mental health industrial complex overmedicates, stigmatizes, and creates long-lasting iatrogenic effects for those most marginalized in society.

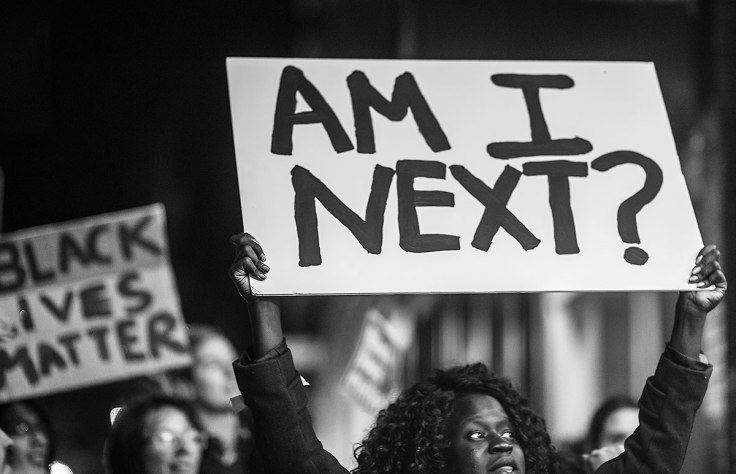

By positioning mental health problems as purely individual issues, the mental health industrial complex depoliticizes distress, effectively conditioning people to overlook structural issues, such as racism and classism. He argues that the mental health field in the United States perpetuates systemic violence, suggests that being human is reducible to our brain chemistry, and ignores context and culture.

“This specific ontology of subjectivity, which defines the entire human experience as a result of brain chemistry, is a singular, restrictive and reductive understanding of all the ways in which humans and their subjectivity can be understood,” Greene writes. “And, this reduction serves a specific political function. That is, it keeps those who are oppressed inward looking and forecloses knowledge of the dominant class as they exert enough force to contribute to extensive suffering and mental illness in the oppressed.”

Greene goes on to explain that endorsing this biomedical philosophy of life, which obscures structural violence, props up the mental health industrial complex as a business, built upon a model in which suffering is exploited, and billions of dollars of revenue are brought in. Greene writes:

“This specific kind of colonization of consciousness (i.e., ideology or false consciousness), by the mental health industrial complex contributes to what the professor of humanities, Dr. Robert Zaslavsky, has coined as the current ‘culture of incapacity’ and elicits mantras of self-blame while exploiting humans as patients for the bottom-line dollar. In short, the definition and diagnosing of mental illness is political.”

At the same time, the inner workings of the mental health industrial complex and the state are overtly evidenced by the extensive coordination of services between mental health facilitates and police, prison systems, and education systems.

In this paper, Dr. Greene shares his first-hand experiences of the mental health industrial complex as a therapist working with disenfranchised individuals in the Northeastern United States. To describe the complex dynamics, he analyzes three case studies of black male patients.

Greene suggests that the patient population he works with represents individuals who have been placed within “zones of social abandonment.” Drawing from the work of Biehl, he summarizes this abandonment process as one in which “persons are marginalized to the fringe of society wherein they are further exploited, oppressed or abandoned with little to no recourse.”

He connects this to his work at the mental health clinic, writing that it represents one of these zones of abandonment. He goes on to describe overt abuses of power by the clinic staff that he felt paralleled the damaging sociopolitical dynamics taking place within the wider community setting.

For example, he attempted to confront a staff member who regularly slept with their patients. The staff member was indifferent to this confrontation, inviting him to report him because he “had no proof.” Indeed, when Greene made the report, he was informed that if he did not personally see or witness anything, the authorities could not act.

Greene recounts a disturbing, overtly racist comment made by a senior psychiatrist:

“On one unforgettable day, a senior psychiatrist said, in reference to poor black patients, ‘We should just drop a bomb on this whole community and end their suffering. They are evil and broken. They can’t help themselves. All they do is act like wild animals, and there is no way to help them.’ I was so stunned by the comment. The only phrase I could utter was ‘How can you say something like that?’ To which, he replied, ‘Because it’s true. They can’t be helped.’”

The clinic functions on a model of providing quick fixes, he writes. Medication is administered liberally. Greene recalls how patients would often forego therapy sessions, yet lines would build in the medication refill room.

The fleeting nature of the psychotherapy relationship is enforced by a system designed to “get as many patients out and in as possible,” according to the clinic director. As a result, patients who would most likely benefit from long term, supportive relationship are more likely to re-experience abandonment in therapy.

Clinical conceptualizations of client distress were not only saturated by biomedical understandings of individuals as chemically disordered but were influenced by racially biased misperceptions. For example, young black boys were criminalized, perceived as older, and described as aggressive.

Greene provides specific details of the entrenched racist and classist functioning of the clinic and its employees when outlining the three cases. In one of the cases, he discusses and analyzes the clinic’s response to an 8-year-old black boy referred to in the paper by the name of John.

John was given diagnoses of ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD). He had missed a lot of school in the last year and had been expelled from a previous school. The psychiatrist described John’s case as hopeless, with the possible exception that the “miracle of medicine could cure him.” Therefore, they prescribed John aripiprazole, an antipsychotic associated with adverse effects such as headaches, weight gain, insomnia, and anxiety. John developed all of these side effects. He developed a more subdued, quiet disposition. Although his grades appeared unchanged, he was able to attend school and “sit still.” He was prescribed trazodone in response to his drug-induced sleep difficulties.

Dr. Greene describes how his conceptualization of John differed from that of the clinic’s formulation. As he learned about how John’s father was incarcerated, he understood John as demonstrating the effects of trauma rather than ADHD or ODD. Greene calls attention to his hesitance to develop close relationships, despite his pain and desire for care, as a valid presentation, given his experienced relational inconsistency. John’s mother opened up to Greene about her suffering, hopelessness, and short temper. She was a single mother, working multiple jobs. She expressed guilt and shared that this manifested in physical abuse of John, sharing one instance in which she hung him in the closet by his hands, beat him with a belt, and called him racial slurs. Greene recognized this as a manifestation of intergenerational trauma and the hopelessness generated by slavery, historically, as well as the modern-day systems that sustain racism and classism.

Greene writes that his attempts to contest the clinic’s mode of operations were not effective. He writes that “the psychiatrist dismissed the family situation as ‘normal’ for ‘black people.’ On multiple occasions, he told me that ‘they have no sense of family integrity.’ This type of racist statement completely disregarded the greater political dynamic by which black people have been dominated for centuries, and from which currently black people continue to suffer, thus making the cohesion of a family structure problematic and difficult.”

He goes on:

“Within our case consultations, protesting such racist statements was not effective. On several occasions, I attempted to discuss alternative dimensions to the patient’s suffering including economic hardship and historical context.”

Ultimately, such protests were dismissed, and the psychiatrist’s scientifically objective stance was reinstalled as a defense to considering alternatives.

“These concerns were met with a nodding agreement and then a change of subject, or, the phrase uttered in response was, ‘yeah, but there’s nothing we can do about that’, or stated disagreement. On one occasion, I approached a psychiatrist privately to ask if he thought his opinion was obscured by racial and class bias, and he scoffed in reply, stating that his ‘objectivity’ was ‘intact’ and that (i.e., race and class) ‘did not matter’”

As Greene goes on to depict his experiences across the additional two cases, he notes how the clinic’s myopic focus on personal shortcomings that relies upon racist and classist ideologies perpetuates systemic violence. This myopic focus on the individual’s deficits simultaneously renders the complex nature of their suffering invisible. He writes:

“It appeared that both racism and classism were entrenched in the functioning of the clinic and in the minds of its employees. These ideas and attitudes were not susceptible to critique. Accordingly, this structural violence perpetrated on the poor and the marginalized clients had less to do with inner-personal problems — which were also present — and much more to do with a system that seemed to have both given up on them and related to them by means of an antagonistic dynamic. This subaltern population had no voice and was, therefore, invisible.”

Greene writes that although these experiences were unsettling, they are perhaps not surprising. Very little training is afforded to examining the insidious impact of racism and classism in our society, much less its foundational role in structuring mainstream mental health services.

Greene supplements his writing consistently with statistics that document an ongoing trend of the pathologization and psychologization “ (i.e., converting socio-political problems into problems of personal failure)” of poverty and other forms of marginalization. He ends discussing the deep-seated realities of how structural violence has permeated within and perpetuated by the mental health industrial complex:

“The clinic and the therapies provided therein act as a tool of systemic oppression. Unless clinicians actively work against dominant racial inequalities and institutional forms of oppression, our tools work to perpetuate and exacerbate them.”

“Focusing on multiculturalism, empathy, understanding the ‘other’, identifying everyday violence and microaggressions, and recognizing the potential for empowerment are all helpful to create greater awareness and consciousness of the problems one faces, but institutional changes which impact the psychology of disenfranchised persons are more likely to happen by means of a radical confrontation with a racist and classist system. The social world needs to be changed, too.”

****

Greene, E. M., (2019). The Mental Health Industrial Complex: A Study in Three Cases. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 0022167819830516. (Link)