Published by The Economist

Going vegan for two-thirds of meals could cut food-related carbon emissions by 60%

IT IS NO secret that steaks and chops are delicious. But guzzling them incurs high costs for both carnivorous humans and the planet. Over half of adults in both America and Britain say they want to reduce their meat consumption, according to Mintel, a market-research firm. Whether they will is a different matter. The amount of meat that Americans and Britons consume per day has risen by 10% since 1970, according to figures from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation.

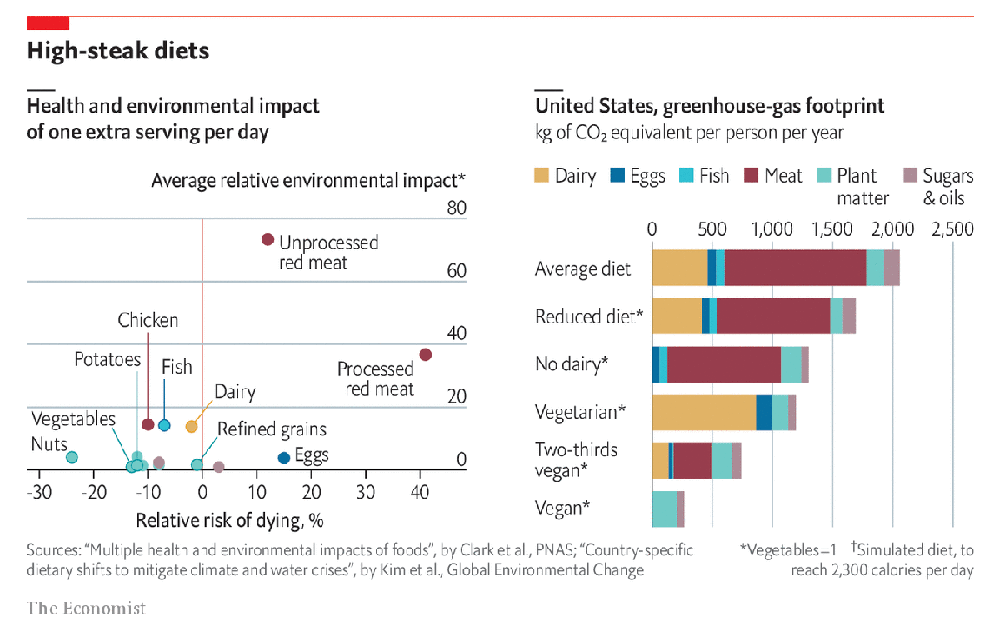

People who want to eat less livestock—but who can’t quite bring themselves to exchange burgers for beans—might take inspiration from two recent academic papers. A study published this week by scientists at Oxford University and the University of Minnesota estimates both the medical and environmental burdens of having an extra serving per day of various food types. The health findings were sobering. Compared with a typical Western adult of the same age who eats an average diet, a person who guzzles an additional 50g of processed red meat (about two rashers of bacon) per day has a 41% higher chance of dying in a given year.

Meat has an even starker impact on the environment. Compared with a 100g portion of vegetables—the standard serving size considered in academic papers—a 50g chunk of red meat is associated with at least 20 times as much greenhouse-gas emitted and 100 times as much land use. Averaged across all the ecological indicators the authors used, red meat was about 35 times as damaging as a bowl of greens.

However, a newly converted vegetarian who replaces every 50g of beef she usually eats with 100g of kale would soon be famished. A standard portion of greens contains far fewer calories than a slab of meat. So an aspiring herbivore would have to eat far more servings of salad than the number of burgers she has forsaken.

Earlier this year a group of academics, based mainly at Johns Hopkins University, simulated the environmental effects of such substitutions. They used consumption and trading data from 140 countries to estimate which foodstuffs people might switch to in order to help the planet, and came up with several hypothetical diet plans. These would allow people to achieve the recommended amounts of energy and protein in various ways.

Giving up meat makes a big difference. For instance, compared with an American who eats 2,300 calories of a typical mix of foods, one who became vegetarian would knock 30% off their annual greenhouse-gas emissions from eating. But dairy, produced by methane-emitting cows, is still costly. Environmentally conscious omnivores can get similar reductions in their carbon footprints by cutting out milk and cheese.

A better option still would be go to vegan for two-thirds of meals, while still occasionally indulging in animal products. Doing so would cut food-related greenhouse-gas emissions by nearly 60%. Absolute veganism, unsurprisingly, is the most environmentally friendly. Die-hard leaf-eaters can claim to have knocked off 85% off their carbon footprint.