Written by Bob Berwyn / Inside Climate News

Annual reports from European and Japanese climate agencies show that last year was yet another marked by extraordinary global heat.

European climate scientists have tallied up millions of temperature readings from last year to conclude that 2020 was tied with 2016 as the hottest year on record for the planet.

It’s the first time the global temperature has peaked without El Niño, a cyclical Pacific Ocean warm phase that typically spikes the average annual global temperature to new highs, said Freja Vamborg, a senior scientist with the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, who was lead author on its annual report for 2020.

That report shows the Earth’s surface temperature at 2.25 degrees Fahrenheit above the 1850 to 1890 pre-industrial average, and 1.8 degrees warmer than the 1981 to 2010 average that serves as a baseline against which annual temperature variations are measured.

In the past, the climate-warming effect of El Niño phases really stood out in the long-term record, Vamberg said. The 1998 “super” El Niño caused the largest annual increase in global temperatures recorded up to that time, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“If you look at the 1998 El Niño, it was really a spike, but now, we’re kind of well above that, simply due to the trend,” Vamberg said.

El Niño can warm the planet’s annual average temperature by about 0.15 degrees Celsius, so the global temperature could spike to yet another new record next time the central equatorial Pacific swings to that warm phase, said Jennifer Francis, a scientist with the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts.

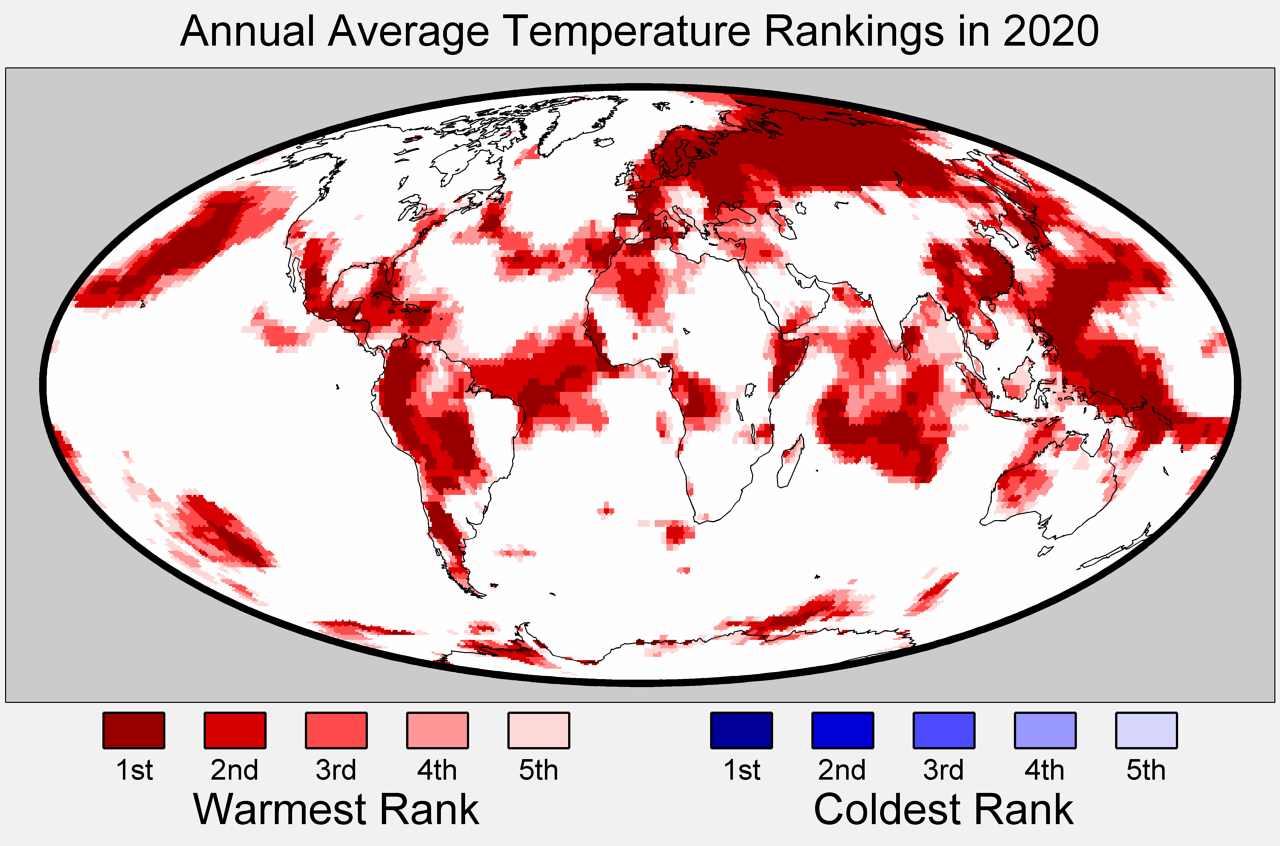

Part of 2020’s record heat can be attributed to persistent warmth in the Arctic and northern Siberia, where the annual temperature was 10.8 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than average for the year, Vamberg said.

Europe recorded its warmest year on record: 0.72 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than 2019 and 2.9 degrees warmer than the 1981 to 2010 baseline. Autumn was especially hot on the continent, running 4 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the baseline for the first time ever.

The last six years were the six hottest recorded on the planet, and 2020 closed the warmest decade on record.

In the records of the Japanese Meteorological Agency, which released its annual report last week, 2020 beat out 2016 as the planet’s warmest year, running 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit above the 20th century average. It was the fifth-warmest year on record for the U.S., according to the 2020 U.S. national climate summary released by NOAA on January 8. Its annual global climate report and other major climate studies are due in the next week or so, including those from NASA and the United Kingdom Meteorological Office. Their results are expected to be within a tenth of a degree of each other.

Each of the agencies uses the same general set of temperature readings from thousands of weather stations spread across continents and oceans, but they sometimes reach slightly different results, because they calculate the data in different ways. That’s especially true with data from polar regions, where readings are sparse.

The final numbers rarely differ by more than a few hundredths of a degree, but in a year in which the results are very close to previous readings, that can affect the ranking. Once all the figures are out, the United Nations World Meteorological Organization compiles them and releases an annual report that includes the closest thing to an official global temperature measurement. The WMO should release its report later this month.

The small differences don’t call any of the measurements into question, Vamberg said. When taken together, especially over a period of five or 10 years, they reinforce each other and show the inexorable, long-term warming trend caused by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, she said.

“I wouldn’t make a call saying one is better or different,” added Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, head of climate science with Climate Analytics and Humboldt University in Berlin. “They just reflect different ways of constructing a temperature record.”

Last year’s record or near-record reading was widely expected and forecast for months, due to a steady string of monthly records.

“What we are seeing is pretty much in line with our expectations,” he said. “If it was an El Niño year, we would expect an additional spike on top of human-made climate change.” In comparing years on a short timescale, he added, natural annual variations can still override the signal of human-caused warming.

“An individual record year is not the core message of climate science,” Schleussner said. “It will continue warming until CO2 emissions meet net zero. Any individual year record is a reminder we are still increasing the level of greenhouse gases, which means Earth will keep getting hotter.”

The dramatic impacts of 2020’s record warmth were also not unexpected. Blistering heat waves on every continent, a hyperactive Atlantic hurricane season and wildfires that raged from Australia to the Arctic have all been attributed to global warming by peer-reviewed research.

The various global annual temperature compilations help clarify the picture of a warming planet, said Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder and the University of Auckland, New Zealand.

“The consequences are clear,” Trenberth said. “More heatwaves, including marine heat waves, stronger, bigger, longer lasting hurricanes, heavier rainfalls and snowfalls and stronger droughts and wildfires.”