Written by Ashley Edes / The Revelator

Images of chimpanzees and other species appear cute, but they may actually depict animals in dangerous situations. Here’s how to tell what’s safe to share — and how that helps conservation.

Whether you find it fascinating or disquieting, people recognize the inherent similarities between us and our closest primate relatives, especially the great apes. As a primatologist I regularly field questions ranging from how strong gorillas and chimpanzees are (very) to whether monkeys throw poop (not yet observed in the wild) to how smart they are (let’s just say I can’t compete with their puzzle-solving abilities).

Interspersed with the fun and interesting facts I share about primates, I also try to help people become more discerning consumers of animal photos, videos and other content, especially on social media. A little bit of context can help people avoid unintentionally supporting wildlife trafficking or other harmful practices through a like or a share.

We’ve all seen images and videos of primates that go viral — a chimpanzee bottle-feeding a baby tiger, a monkey having makeup applied, slow lorises eating rice balls and holding tiny umbrellas. Most recently, widely circulated videos have shown juvenile chimpanzees dressed in clothes and hugging former caretakers or scrolling through Instagram on a smartphone. Whether due to their similarities to us or to the fact that most of our animal experience is with domesticated species, many viewers erroneously believe these pictures and videos are not only cute and innocuous but that they depict animals in positive, healthy situations.

Unfortunately, this is often not the case.

One of the best ways to gauge animal welfare in zoos and sanctuaries (and more broadly on social media) is to use the Five Freedoms, which were first presented in 1979 by the UK Farm Animal Welfare Council. Essentially, positive welfare means animals experience:

- Freedom from hunger or thirst — access to water and species-appropriate food;

- Freedom from discomfort — appropriate environments with shelter and resting areas;

- Freedom from pain, injury, or disease — diagnosis, treatment and prevention when possible;

- Freedom to express normal behaviors — enough space and appropriate social housing to facilitate these behaviors (within reason, as not every natural behavior can be accommodated);

- Freedom from fear and distress — avoid mental suffering.

With these Five Freedoms in mind, you can pick out some of the welfare concerns that wildlife experts see in these viral images and videos. Wearing clothing is not a normal behavior and is an immediate red flag. Primates that are strongly bonded to humans often are not in appropriate environments, meaning those locations and situations aren’t designed to help them express normal behaviors with members of their own species. (Occasionally humans in zoos and sanctuaries must care for neglected or orphaned infants, but these animals are socialized and housed with members of their own species as soon as possible.)

Other issues may be harder to recognize, which is why the expertise of those with specialist knowledge is so valuable. For example, videos of slow lorises frequently violate the Five Freedoms — rice balls are not appropriate food sources for this species and those shown reaching for tiny umbrellas are exhibiting a fear display, information about their biology and behavior the public would not typically have.

While these problems are not unique to primatology, our abundant similarities lead people to believe they can accurately judge how their evolutionary cousins are feeling. But those big open mouth “smiles” aren’t expressions of happiness, they’re “fear grimaces” (formally termed ‘silent bared teeth displays’), which primates display to signal subordination to a larger, stronger individual, usually in contexts where aggression has occurred or is likely. These expressions are especially prevalent in the entertainment and greeting card industries; I encourage you to think about the treatment received behind-the-scenes to get displays of submission and fear in front of a camera.

Many believe that engaging with social media posts such as these through liking, sharing or even commenting has no impact on animal conservation. But these videos and images actually do threaten species, many of which are already in peril. Likes and shares are noted by those in the exotic pet trade, and comments like “I want one” encourage viewing wildlife as suitable pets and fuels the continued removal of endangered species from their homes.

Research by primate conservationists has documented the devastating effects social media can have on primate populations (you can read some of the scientific papers for free here, here, here and here). For example a 2015 study by Katherine Leighty and colleagues demonstrated that viewing pictures of primates in a stereotypical office setting both increased people’s desire to have these animals as pets and decreased their likelihood of believing the animals to be endangered. By comparison, primates depicted in forests or away from humans were perceived as happier. This and studies like it demonstrate that the pictures and videos we see on social media do affect public perception.

It’s important to understand just how drastically the pet trade can threaten the survival of vulnerable and endangered species. For example, infant chimpanzees are targeted for the pet trade because adults are dangerously strong and can be very aggressive. Because adults will fight to protect them, whole troops are regularly killed to capture one or two infant chimpanzees. These infants rarely survive long enough to be sold, either due to the traumatic experience, the poor conditions following capture, or a combination of both.

There are many other awful realities of the primate pet trade, such as slow lorises, which are the only venomous primates, having their teeth cut out with nail clippers so they cannot bite (check out more on the plight of slow lorises at the Little Fireface Project).

You don’t have to be an animal welfare expert to fight back against the pet trade. Below are simple, easy steps individuals or organizations can take to support the conservation of endangered species.

- Don’t like, share or comment positively on questionable media. Look for those red flags indicating the Five Freedoms of animal welfare are being violated. If you aren’t sure, you can consult this guide or reach out to a primatologist or wildlife biologist — there’s a whole big community of us on social media and we’re happy to help (you can find me on Twitter at @ashley_edes).

- If you are following accounts that regularly share questionable media, unfollow them.

- Challenge others who share questionable media. You can share this essay or some of the many other excellent ones that have been written on this topic (see pieces by the Jane Goodall Institute, DiscoverWildlife and Mongabay).

- Do not purchase greeting cards or items depicting animals in poor welfare situations (e.g., wearing clothes, smoking, riding bicycles) and educate others if you receive such items.

- Avoid tourist activities allowing close interaction with wild animals. While there are exceptions, in many of these situations the animals are drugged or cruelly trained to be docile and pose for pictures with tourists (see this piece from National Geographic and recent research on pet lemurs and wildlife tourism for more).

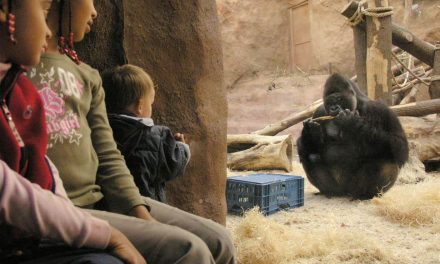

- Follow reputable zoos and sanctuaries for wildlife content. Zoos and sanctuaries share amazing pictures and videos on social media every day. Engaging with these posts spreads media that have a positive impact on captive animal welfare and the conservation of their wild counterparts. One of the easiest ways to identify reputable organizations is to look for accreditation from AZA, ZAA, BIAZA, EAZA, WAZA, GFAS and/or NAPSA. These organizations donate millions to conservation efforts every year, and institutions accredited by them have higher standards of animal care.

When we truly care about wildlife, we want them to thrive. As difficult as it may be, we need to make sure our desire to be near to and connect with wildlife doesn’t jeopardize their ability to live and thrive in the wild. Rethinking and changing our engagement with wildlife content on social media — not just as individuals but as a culture — can have real, positive impacts on the animals we are trying to save.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.