Written by Simon Worrall / National Geographic

The author of a new book also says that animals can feel empathy, like the humpback whale that rescued a seal.

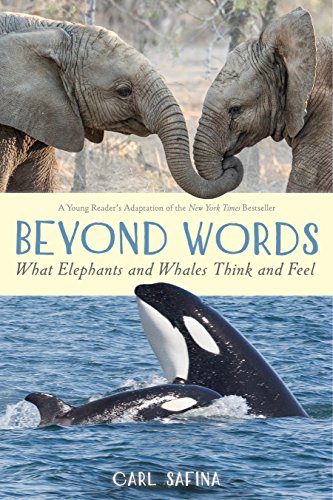

Do animals feel empathy? Does an elephant have consciousness? Can a dog plan ahead? These are some of the questions that award-winning environmental writer Carl Safina teases out in his new book, Beyond Words: How Animals Think and Feel.

Ranging far and wide across the world, from the Ambroseli National Park in Kenya to the Pacific Northwest, he shows us why it is important to acknowledge consciousness in animals and how exciting new discoveries about the brain are breaking down barriers between us and other non-human animals.

Speaking from Stony Brook University on Long Island, New York, where he is a visiting professor in the school of journalism, he explains how elephants routinely display empathy; why U.S. Navy underwater tests in the Pacific Northwest should be stopped; and how his own pet dogs prove his theories.

Your book suggests that animals have thought processes, emotions, and social connections that are as important to them as they are to us. Why is it important to know this?

It’s important to know who we are here on Earth with. We talk about conservation of animals by numbers, but those are just numbers. Watching animals my whole life I’ve always been struck by how similar to us they are. I’ve always been touched by their bonds and been impressed—occasionally frightened—by their emotions.

Life is very vivid to animals. In many cases they know who they are. They know who their friends are and who their rivals are. They have ambitions for higher status. They compete. Their lives follow the arc of a career, like ours do. We both try to stay alive, get food and shelter, and raise some young for the next generation. Animals are no different from us in that regard and I think that their presence here on Earth is tremendously enriching.

You state that consciousness is not merely a human experience and cite the Cambridge Declaration of Consciousness drafted in 2012. Tell us about this new interpretation and how it relates to our fellow creatures.

The issue over consciousness, like many aspects of animal behavior, is confused by a lack of definitions people agree on. We tend to use the word consciousness to mean a variety of different things. Some people say if you can plan years ahead it shows consciousness, but that just shows planning.

If you’re having a mental experience, you are conscious. The question really is, do other species have mental experiences or do they sense things without having any sensation of what they are experiencing? Like a motion sensor senses motion but it probably doesn’t experience that it senses motion. Animals do—they react to movement: fight or flight or curiosity.

It is incredible to me there is still a debate over whether animals are conscious and even a debate over whether human beings can know animals are conscious. If you watch mammals or even birds, you will see how they respond to the world. They play. They act frightened when there’s danger. They relax when things are good. It seems illogical for us to think that animals might not be having a conscious mental experience of play, sleep, fear or love.

Dogs, the author says, know exactly who we are and are often very, very happy, just like this Labrador retriever at Moosehead Lake, Maine seems to be.

PHOTOGRAPH BY HEATHER PERRY, NAT GEO IMAGE COLLECTION

So why are many scientists adverse to the idea that animals have consciousness?

In the beginning there was almost no neurology, nothing was known of how mental processes worked. Animal behavior was based on fables, like foxes are clever, tortoises are persistent. So scientists said, “All we can know about animals is based on what they do. We can only describe what they do. We can’t know anything about their minds.” Unfortunately, that hardened into a straightjacket assumption that if we can’t know anything about their minds, we can’t confirm consciousness.

Meanwhile, people have spent decades watching wild animals. People who watch wild animals don’t question whether they’re conscious or not because we see incredible intricacies of behavior and vast ranges of personalities. I’m talking about vertebrates: mammals like elephants and cats, but also birds.

It’s very obvious that animals are conscious to those who observe them. They have to be in order to do the things they do and make the choices that they do, and use the judgments that they use. However, in laboratories the dogma persists: don’t assume that animals think and have emotions–and many scientists insist that they do not.

With the public, I think it’s quite different. Many people simply assume that animals act consciously and base their belief on their own domestic animals or pets. Other people do not want animals to be conscious because it makes it easier for us to do things to animals that would be hard to do if we knew they were unhappy and suffering.

Elephants play in Damaraland, Namibia. “Researchers spend decades watching these creatures and see individuals,” author Carl Sarafina writes.

PHOTOGRAPH BY MICHAEL POLIZA, NAT GEO IMAGE COLLECTION

I love how you reveal the important aspects of play in the animal world and the relationship between adults and children, so similar to our own.

When the public sees wild animals they feel lucky to see elephants, or they might go to Yellowstone and see wild wolves. Researchers spend decades watching these creatures and see individuals. Many researchers have names for the animals and recognize the different personalities. Some are bold; some are shy. Some are more aggressive; some are mellower; some babies are much more assertive.

They see that first time mothers aren’t as sure about what to do, and experienced mothers are more relaxed and confident. They see that some wolves are very assertive and aggressive and other wolves forbear. If there is a fight, some wolves will kill other wolves, but other wolves won’t, even when they beat them in a fight.

What you see when you actually get to know wild animals is very different from a casual sighting. If you saw human beings doing nothing but drinking water or running around a field, would you think that is all there is to human beings? If you know the people drinking the water or running around, you have a different experience watching them.

A mother humpback whale and baby dive in Pacific waters off Maui. There is a documented account of a humpback sweeping a seal on its back, away from attacking killer whales.

PHOOTGRAPH BY WOLCOTT HENRY, NAT GEO IMAGE COLLECTION

Empathy is another characteristic that animals and human beings share. Can you tell us more about how empathy is expressed by animals in extraordinary circumstances—both with humans and other animals?

Many people think that empathy is a special emotion only humans show. But many animals express empathy for each other. There are documented stories of elephants finding people who were lost. In one case, an old woman who couldn’t see well, got lost and was found the next day with elephants guarding her. They had encased her in sort of a cage of branches to protect her from hyenas. Thats seems extraordinary to us but it comes naturally to elephants.

People have also seen humpback whales help seals being hunted by killer whales. There is a documented account of a humpback sweeping a seal on its back out of the water, away from the killer whales. These things seem extraordinary and new to us because we have only recently documented these incidents. But they have probably been doing these kinds of things for millions of years.

Both elephants and killer whales are suffering dramatic losses in their population. Connect these two creatures for us and what challenges they face in the modern world?

I tried to take a break from writing about conservation to write about what animals do in their natural lives. I focused on three of the most protected populations of animals in the world—elephants in national parks in Kenya, wolves in Yellowstone National Park, and killer whales in the Pacific Northwest; in all three cases I found that these protected animals are still being killed by people.

Elephants have been undergoing a tremendous slaughter since 2009, when the powers that be decided China could import ivory from dead elephants. As a result, elephant populations are being devastated by poachers throughout Africa and Asia.

PHOTOGRAPH BY EMORY KRISTOF, NAT GEO IMAGE COLLECTION

A scientist studying animal survival shoulders a wolf at the United States Naval Arctic Research Lab in Barrow, Alaska.

In the case of the wolves in Yellowstone National Park, the U.S. removed endangered species status from wolves outside the parks. So, when wolves from the parks stray outside, they’re often shot and it is usually the alpha pack leaders who are killed. When wolf packs lose their alpha male or female, they often break up. The younger wolves don’t have the knowledge to survive that adults have.

Killer whales have very poor reproduction because the salmon stock they depend on is so depleted that they don’t get enough food and are not in good enough condition to bear young. The young don’t survive well, either. Killer whales are full of toxic chemicals that they get from their food and the polluted waters where they swim around Washington State and West Coast of the United States. Even though they’re endangered and they’re supposed to be afforded the strictest protections, the Navy also continues to test live bombs in areas where these whales swim.

One pod that desperately needed a young, healthy female had their only young female killed by massive hemorrhaging in her ear canals. A Navy bomb explosion was recorded on the listening devices of the whale researchers the day she died. It’s very distressing that even when we are supposedly protecting these animals they’re not being protected by our own government.

Do you have animals in your everyday life? If so, tell us how they confirm or disprove your theories.

I was never much of a dog person because I was interested in free-living, wild animals, but I have two dogs now and I cannot believe how much I love these dogs and how much they are part of our family. They know exactly who we are. They know who strangers are. They are often very, very happy. Occasionally they get frightened by things that are strange or they aren’t sure what’s going on.

The only thing they cannot do is speak to us in full sentences, but they communicate all the time. They know what they would like to do and they can plan a little bit. They may not plan what they’re gonna do next week, but they know when they want to go out or when they want to get us to take them out for a run.

When we take them to a certain beach, they know exactly what the routine there is, even if we haven’t been to that beach in months. When we take them over to my mother’s, they remember that the shed in her backyard has cottontail rabbits under it and they always run straight to the shed to investigate.

You use the term “vivid” to describe the lives of animals. Explain.

I’ve studied wild animals a lot and I’m always struck by how extremely alert they are and how well they sense what’s going on around them. They’re much more aware, compared to humans. Modern day humans go outside and don’t see, hear or sense very well. Our senses have dulled over thousands of years of civilization and settled living. I think that an animal’s experience of life is much sharper and clearer. That’s why I use the term “vivid”.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter.