Written by Paris Williams, PhD

(originally published at Mad in America)

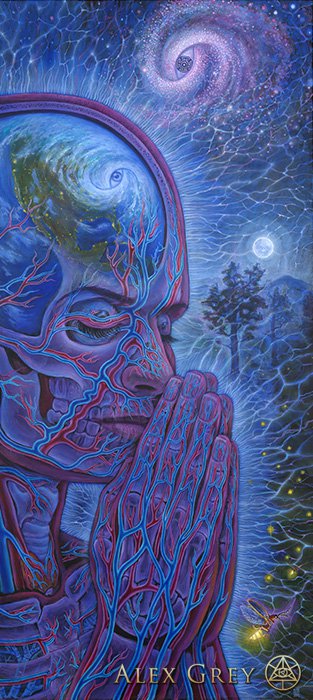

Painting by Alex Grey

Over the years of my explorations into psychosis and human evolution, a very interesting irony became increasingly apparent. It is well known that people who fall into those deeply transformative and chaotic states typically referred to as “psychosis” often feel at different points throughout their journeys that they have received a special calling to save the world, or at least the human race. Indeed, this experience played a particularly prominent role in my own extreme states, as well as within those of at least two of my own family members. From a pathological perspective, this is often referred to as a kind of “delusion of grandeur,” though in my own research and writing, I have come to feel that the term “heroic (or messianic) striving” is generally more accurate and helpful. The great irony I have come to appreciate is that while I think it’s true that these individuals are often experiencing some degree of confusion, mixing up different realms of experience (for example, mixing up collective or archetypal realms with consensus reality, or confusing unitive consciousness with dualistic/egoic consciousness), I have come to feel that perhaps the key to saving the world, or at least the human species, may in fact actually be revealed within these extreme experiences. To better explain this, let me first go over some key concepts.

Rethinking the Self

First of all, we need to reconsider what we mean by the term “self.” The twentieth century represented a real turning point for Western science in that it began to embrace a more holistic paradigm, in essence taking steps towards a paradigm established much earlier within the nondual traditions of the East (such as Taoism, Buddhism and the Vedic traditions) and even earlier within indigenous society. Quantum physics began to recognize just how deeply interdependent and interconnected the universe really is, capturing this with terms such as entanglement and nonlocality. Contemporary systems theory such as chaos theory and complexity theory similarly began to embrace this more holistic understanding of our world, drawing on important concepts such as Ilya Prigogene’s dissipative structure, which refers to the paradoxical way in which living entities maintain their existence across time while energy and matter continuously flow through them—similar to what we see in those little whirlpools standing above the drain of an emptying sink, in that all of the water that makes up its structure is continuously flowing through it and being replaced. Another term used extensively within these systems theories, and one that is particularly relevant to our discussion here about the “self,” is the term holon.

A holon essentially refers to what we generally think of as a living organism, but more precisely, it can be seen as a dynamic entity with three intrinsic qualities: (1) It is a self organizing system, exhibiting a kind of intrinsic consciousness or intelligence; (2) it is a dissipative structure, in that while it is able to maintain a relatively constant structure across time, it is also highly dynamic as it continuously exchanges matter and energy with the environment; and (3) it is irreducible, in the sense that any attempt to reduce it will simply result in the cessation of its existence. Although irreducible, a holon can merge symbiotically with other holons to emerge (another key concept within this holistic framework) into an altogether new holon of a higher order of complexity. This higher order holon is much more than simply the sum of its parts (the holons that compose it) in that it exhibits altogether new qualities that were simply nonexistent within the lower-order holons.

To put the idea of a holon into more concrete terms, we can say that an atom is a holon, which in turn merges with other atoms to form a molecule, a higher order holon that is much more than simply the sum of the atoms that compose it. Molecules in turn may merge symbiotically to create a living cell, what is generally thought of as the simplest living organism (a bacteria), in that some degree of consciousness and volition have become readily apparent. These in turn have merged to form yet another holon of still a higher order of complexity, the nucleated cell; and from these have emerged a still higher-order holon, the multi-celled organisms—the myriad fungus, plants and animals in our world. Certain kinds of groups of these individuals also self organize in ways that could arguably be thought of as higher order holons in their own right—flocks of birds, herds of deer, human families and tribes, an entire species, etc. Complex mergers of many different kinds of holons form ecosystems, which can be considered still higher-order holons. And finally, we recognize that out of a symbiotic relationship between the many different ecosystems of the Earth has emerged the biosphere. The well known NASA scientist, James Lovelock, has given the biosphere the name Gaia to signify that our entire biosphere can be seen as a single conscious and intelligent living organism in her own right, indeed the highest order holon on our planet.

Reversing this order of complexity is similarly illuminating, demonstrating that any attempt to reduce a holon to its parts merely results in an assemblage of lower-order holons, with the original holon itself having ceased to exist. For example, if a biologist kills a mouse in an attempt to better understand it in some way, all that remains is a collection of individual cells, some of which may continue to exist as individual cells, but which no longer work together symbiotically with the other cells to manifest as the more complex being (the mouse). The mouse as a living being, a holon, with all of its unique qualities, is no more.

So when we consider the concept of a self from this perspective, we find that our universe essentially consists of a hierarchically arranged array of holons arising from and embedded within a unified field. Lao-Tzu, writer of the Taoist text, the Tao-te Ching, said, “Tao [translated literally as ‘the way’] produced the One. The One produced the two. The two produced the three. And the three produced the ten thousand things” (Johanson & Kurtz, 1991, p. 1).

The Pros and Cons of Self Consciousness

By observing the behaviors of any living organism—whether it be a humble bacteria, a mighty redwood, or other members of our own human species—we can see clear signs of consciousness and intelligence, which I’m defining as simply the capacity to be aware of one’s environment, to make some kind of meaningful evaluation of it, and to then respond accordingly. What’s less clear is the degree to which different organisms are self conscious—aware of being aware—although it is quite clear that we humans have developed a significant capacity for self consciousness, and that this attribute brings with it both great rewards and serious risk.

On one hand, such a high degree of self awareness allows us to deeply appreciate the wonder of life and our universe. Indeed, we can recognize that our existence represents the achievement of the universe in having developed the capacity to contemplate itself. I find it difficult to conceive of anything more awesome than this. But on the other hand, such self consciousness brings with it a vulnerability to becoming profoundly confused, especially with regard to selfhood. It becomes all too easy to overly identify with the self only at the level of this particular self-aware holon, what is sometimes referred to as the personal or egoic self—that self that we typically refer to when we use the words “me,” “myself” and “I.” And along with this, we are at risk of losing sight of the fact that this personal self is merely one order of selfhood among many other orders of selfhood, as discussed above: at lower orders of complexity, the community of trillions of cells who have merged their collective wisdom and resources to manifest as this personal self, with each of these cells in turn being composed of a merger of yet simpler selves—the bacteria; and at higher orders of complexity, the communities, ecosystems and ultimately the entire biosphere of which we are part. Losing sight of this broader selfhood is not only extremely limiting, but also potentially extremely destructive.

The Breakdown of a Self

An example of the potential destruction that may occur when one member of a holon “forgets” that it is in fact such a member is in the case of cancer. In cancer, what we essentially find is an individual cell within a multi-celled organism that, for whatever reason, “forgets” it is a member of this more complex organism. We can say that its self identity has constricted radically, and it now identifies only with its personal self. Therefore, it still retains its innate tendency to meet its own needs and maintain its own survival, but it no longer contributes to the survival of the larger organism; and since it continues to be nourished by the larger organism while essentially not giving anything back, it develops a great capacity for autonomous reproduction and growth, but all the while increasingly interfering with the functioning of the larger organism. And as is well known, while cancer represents a period of very successful growth for the self-identified cells, if the organism is unable to either destroy these cells or regain their cooperation, the entire organism is likely to die, along with the cancer cells. Therefore, we can say that by losing sight of their broader selfhood, these cancer cells enthusiastically “thrived” their way all the way to their own demise.

Does this sound familiar? In the very same way that single cells live as symbiotic members of the larger multi-celled organism to which they belong, the human species can itself be seen as a holon living in a symbiotic relationship with other holons to form the higher-order holons of ecosystems and ultimately the entire biosphere, Gaia. And just like the case of the cancer cells, the human species has collectively forgotten about this symbiotic arrangement, this broader order of selfhood, and has become consumed with only its own survival at the species level (and at times this self identity is constricted even further to that of only a particular society, race, family, or even nothing more than the individual human being). And just as in the case of cancer, because now this particular holon is consumed only with its own survival while continuing to be fed by the larger organismic systems in which it is embedded, it initially reproduces and grows radically. However, also just as with the cancer cells, its own rampant growth combined with the underlying ignorance of its broader selfhood will ultimately lead to its own demise, as well as the demise of many of its fellow holons, threatening both those at a similar level within the holon hierarchy (other individual organisms and species), as well as higher-order holons such as ecosystems and perhaps even Gaia herself. This may sound farfetched to some, but it’s well established that Gaia has already had some very close calls within her long life, some of which were brought on by certain living organisms themselves, and of course any living system has its limits.

Breaking Down in the Service of Breaking Through

Ironically, the breakdown of a self can sometimes act as a breakthrough to a more sustainable existence of that self, or even in extreme cases, the emergence of an altogether higher order of selfhood –the emergence of holons of a higher order of complexity.

The contemporary evolution and systems sciences have come to recognize that a key component of evolution is the dance between chaos and order. A certain order is required to maintain the existence of holons over time, but when a significant threat of holon breakdown occurs, this can initiate a process of radical and unpredictable change—chaos—as a kind of desperate attempt to renew order when it has been seriously compromised, or even to break through to altogether new levels of order when necessary. So I think that one particularly useful way to define chaos is “a process that utilizes breaking down as a catalyst for breaking through.”

For example, it’s become widely accepted within the evolution sciences that after a very long and relatively stable period of time in the early history of the Earth during which only bacteria existed, a serious crisis emerged caused by the excessive consumption and waste products of the bacteria themselves. Prior to this, the nutrients the bacteria required for their survival were abundant enough that the bacteria were generally able to nourish themselves without bothering each other too much; but now with the population of bacteria exceeding the availability of many of these naturally occurring resources, a chaotic period ensued in which many of the bacteria were forced to consume each other. It’s speculated that some of the consumed bacteria managed to survive even after having been engulfed by other bacteria, and then went on to develop symbiotic relationships within the larger host. This in turn led to the evolution of a new holon of an altogether higher order—nucleated (eukaryotic) cells living as individuals, also referred to as protists. Then, sometime later, the conditions of the Earth had once again become very precarious for its inhabitants, and these single celled protists were forced to come together and live as symbiotic communities of cells, ultimately merging their collective wisdom and resources to evolve into an altogether new holon of yet a higher order of complexity—multi-celled organisms, which have eventually evolved into the fungus, plants and animals that exist today.

It’s important to acknowledge that this process of higher levels of complexity and order emerging from unsustainable conditions and a subsequent chaotic process is generally very risky. It often fails, not resolving successfully or even resulting in the deaths of the participating organisms. Hence the reason we find that it so often seems to require desperate conditions to precipitate such a desperate strategy. And this is where “madness” or “psychosis” comes into the story.

Can Madness Save Us?

I think it’s helpful to recognize that psychosis has both a destructive and a creative, or a chaotic and an ordered, aspect (I’ll use the term “psychosis” here, as I want to emphasize the idea of a particular kind of process occurring, and I feel that the term “madness,” while very helpful in other contexts, is a bit too generic for this purpose). On one hand, psychosis appears to occur as the result of impending breakdown—an individual’s personal paradigm, their experience and understanding of the self and the world, has for whatever reason reached a point in which it is no longer sustainable. But on the other hand, just as in the process of evolution described above, we see inherent in psychosis the utilization of “breaking down” as a kind of desperate strategy for “breaking through,” the utilization of chaos in the service of renewing order or even breaking through to an altogether different order. Yet as we’ve seen within the process of evolution, this can be a very haphazard and risky strategy that may or may not be successful, depending upon the resources and limitations of the particular organism or holon.

Whereas “psychosis” is often considered to be something occurring within a particular individual, I think we need to reconsider psychosis as occurring within the broader understanding of selfhood discussed above. So when an individual is experiencing what is often called psychosis (having anomalous beliefs, perceptions, impulses, etc., that are often extreme and/or unstable), I think it’s important to recognize that this may be the manifestation of a breakdown occurring not only within the individual, but also within the larger holon(s) within which the individual is embedded (the family, society, species, etc.). And I believe that this perspective offers us some compelling insights into how psychosis can be seen as both a warning of serious breakdown within these higher-order holons as well as the key to breaking through.

I think that anyone applying basic critical thinking skills to what can be observed about the state of the world today would be forced to come to the conclusion that we as a species are in serious trouble. No matter which angle you choose to come at it—accelerating climate change, rampant environmental destruction and mass species extinction, expanding and escalating war with over 14,000 nuclear warheads only a button’s push away from detonation—it’s only too clear that we’re skating on very thin ice. By our own doing, we have set the trajectory of our own species as well as that of the other holons of which we are a part toward great chaos. And yet, astonishingly, we collectively carry on with business as usual—increasing the amounts of greenhouse gases we release into the atmosphere, accelerating our destruction of species and ecosystems, expanding our wars and building even more nuclear weapons.

It’s as though we have become completely blind; and in many ways, I believe that’s exactly what has happened. Just like the cancer cells that have become blind to the fact that they are a completely dependent member of the larger organism, the human species has become blind to the fact that it is a dependent member of the broader ecosystems and the biosphere to which we belong, having become consumed with the needs of the more limited selves (one’s nation, one’s family, one’s personal self) at the direct expense of the broader selfhood to which we also belong. In other words, you could say that we have become stricken with a kind of disorder—a disorder of “constricted selfhood,” and unfortunately it appears that we have very little collective “insight” into this disorder.

Interestingly enough, it is perhaps those we deem “mad” who may be in the best position to support our species in developing this insight. Arnold Mindell, who offers the unique perspective of a psychologist steeped in depth psychology, systems theory and modern physics, suggested that:

“In a given collective, the schizophrenic patient occupies the part of the system in a family and a culture that is not taken up by anyone else. She occupies the unoccupied seat at the Round Table, so to speak, in order to have every seat filled. She is the collective’s dream, their compensation, secondary process and irritation” (2008, p. 125).

In other words, although a person experiencing psychosis may be experiencing great confusion and fluctuation between different realms of experience, these extreme states of mind often allow the person to act as a kind of conduit bringing forth the shadow—the unacknowledged, the unspoken, the denied—aspect of the particular system(s) or holon(s) to which they belong. Indeed, there is compelling evidence to suggest that someone experiencing psychosis is often able to perceive the world in a more raw and accurate manner than when in more ordinary states (such as, for example, their capacity to see through the illusion of the inverted face), and to bring forth within their anomalous experiences various valid shadow elements, such as with the prominent “paranoid delusion” of being watched over by government agencies experienced by many such individuals long before Edward Snowden revealed the actual truth of this, the long held apocalyptic themes that are uncomfortably close to what we now see actually unfolding within the world, or the voices of voice hearers that often correspond very closely with certain shadow elements within the individual’s family and broader social systems. Although these anomalous perceptions and beliefs are often exaggerated or distorted to some degree, perhaps it’s time we recognize the shadowy truths so often contained within them, and appreciate that such individuals can serve a very important role in our collective survival by acting as our canaries in the coal mine, helping us to develop insight into our impending breakdown.

It appears that nearly ubiquitous among indigenous societies is the appreciation for the potential gifts of such individuals, and the essential role that they play in maintaining the overall health of the tribe and larger social structures. Referring to such individuals as shamans, seers, visionaries, etc., indigenous societies have long recognized that without reserving an honoured place for such individuals within the social structure, the society is vulnerable to falling prey to increasingly narrow and rigid belief systems, which may ultimately undermine the health and adaptability of the society and lead to its demise (see John Weir Perry’s Trials of the Visionary Mind for what I believe is an excellent exploration of these ideas). When we look around at the state of contemporary human society, with its deepening entrenchment into rigid and dogmatic belief systems, we have to ask ourselves how wise it really is to continue invalidating such individuals as simply “crazy” or “brain diseased” and relegating them to a lifetime of mind-numbing drugs and institutionalization.

So if we consider that individuals who experience psychosis can play a very important role in helping the broader human society in developing “insight” into our unresolved shadow issues and especially the problem of our constricted selfhood, the question then arises, So what do we do about it? And again, I believe that the answer to this dilemma may well lie within the process of psychosis itself. If we consider that the human species is essentially struggling with a “disorder or constricted selfhood,” then it becomes clear that our salvation requires that we undergo a species-wide transformation of the self. Interestingly enough, when we inquire into the subjective experiences of individuals experiencing psychosis, what we so often find is a person grappling with exactly this process—a profound transformation of the self.

My own research (Williams, 2011, 2012) as well as numerous anecdotal accounts suggest that initially when a person enters into a psychotic process, their experience of the self and the world becomes highly chaotic and/or fragmented. However, those who manage to move through this process and experience successful resolution very often find that they arrive at an experience of self and the world that is qualitatively very different than that which existed prior to the psychosis. Many such people report significantly greater wellbeing and a more fluid, expansive and integrated experience of the self. For example, the participants of my own research who have experienced such a resolution all share the following common shifts as having occurred within their personal paradigms when comparing their experience now with what existed prior to the onset of their psychosis:

- A significantly changed spectrum of feelings with more depth and unitive feelings

- An increased experience of interconnectedness

- A strong desire to contribute to the wellbeing of others

- An integration of good and evil (feeling generally more whole and integrated within themselves; and seeing “evil” actions or intentions as simply the result of profound ignorance—especially as problems with constricted selfhood—rather than as anything intrinsic within anyone).

- Appreciating the limits of consensus reality

And they all share the following lasting benefits (comparing their experience after the resolution of their psychosis to that which existed prior to the onset of the psychosis):

- Greatly increased wellbeing

- Greater equanimity

- Greater resilience

- Healthier, more rewarding relationships with others

- Healthier relationship with oneself

In other words, it appears that such an individual often goes through a profound transformation of selfhood in which they emerge with a greater appreciation of the interconnectedness and interdependence of the world, and the inspiration to live in a way that is more in alignment with this shift in their personal paradigm—a way that is likely to be more beneficial for the personal self as well as for the other living organisms and living systems with whom they share the world. It is easy to see that this is exactly the kind of transformation the human species is in desperate need of undertaking—a profound transformative process from a highly constricted experience of the self to an experience of selfhood that is much more fluid, expansive, and humble. But how do we foster such a radical transformation?

To answer this question, I think we first need to look more closely at the state of the human species today. It’s self evident that the human species has collectively become entrenched in an experience of selfhood that is no longer sustainable, a condition very similar to what we see within an individual just prior to the onset of psychosis. It is equally self evident that, generally speaking, chaos and breakdown are rapidly escalating within human society and even within the higher order holons of the world’s ecosystems and biosphere. Again, we find conditions occurring within this higher order holon (the human society and species in general) very similar to that which occurs when an individual is slipping into a psychotic process. So would it not be appropriate, then, to consider that the human species as a whole is sliding into a kind of collective psychosis? And if so, is there some way that we can facilitate the transformation of our paradigm—our collective experience and understanding of the self—towards one that is more flexible, expansive and humble? Or do we simply have to hang on and go for the ride, trusting that a deeper wisdom will somehow see us through?

This is where I believe we may be able to take some guidance from those approaches that have been so effective in supporting individuals going through a psychotic process— residential facilities such as Soteria, Diabasis and I-Ward, the family and social systems approaches such as Open Dialogue, and the shamanic mentoring model we find within indigenous societies. All of these approaches share the belief that in spite of the chaotic and potentially destructive nature of psychosis, there is a deeper wisdom occurring within it that is striving to bring about a deep transformation from an experience of the self and the world that is no longer sustainable to one that is.

The general philosophy of the residential homes such as Soteria, Diabasis and I-Ward is that if a safe and nurturing cocoon is provided to the person—allowing for maximal freedom within a structure that ensures minimal harm and destruction—the psychosis is likely to naturally move through to a full and successful resolution. Applying this approach to the problem of our species-wide psychosis, then, it would make sense that we should strive to create similar conditions within our society at large—maximal freedom (i.e., genuine non-authoritarian democracy) within maximal safety (i.e., strict regulations placed upon harmful industry and excessive greed, while using nonviolent means and effective communication rather than aggression and war to settle our disputes).

The Open Dialogue approach and other family systems approaches directly address the need to create a context of an expanded experience of selfhood, especially in that they generally see psychosis as representing a breakdown occurring within the individual’s immediate social network (the family, close social group, etc.). And they support resolution of the psychosis, and the emergence of a more sustainable order within these various holons, by fostering open and authentic communication between the various members of these holons. In other words, all voices, especially those representing the shadow aspects of these systems, are honoured and brought to the table. This approach draws from the faith in the intrinsic self-organizing capacity of any living system or holon, seeing breakdown as occurring when various members of the system are excluded or ignored, and therefore seeing breakthrough as occurring when all members are included. Applying this approach to the problem of our species-wide psychosis, we again arrive at the conclusion that genuine, all-inclusive, non-authoritarian democracy is likely to be extremely important for our positive transformation. Furthermore, it becomes clear that effective communication and dialogue (both within self connection as well as in connection with others) are essential components of this, and that this dialogical process needs to extend beyond the various political boundaries and divisions we see in the world today to include the entire human species. Following the lead of some indigenous communities today, I would even take this further and suggest that the voices of the other holons within our expanded sphere of selfhood (the other living organisms and ecosystems) also need to be brought to the table.

Finally, indigenous societies generally have a system in which people who go through a psychotic process (sometimes referred to within this context as a shamanic illness) are mentored by others who have already successfully passed through such a process. This is somewhat akin to the various peer support systems we see in place today within contemporary society (peer respites, voice hearing groups, etc.). The potential benefits of this approach are quite obvious—those who have “been there” and have successfully integrated their experiences are often able to provide very effective support and guidance to those who are continuing to struggle with these experiences. Applying this approach to our species-wide psychosis suggests that those who have gone through psychosis and other extreme states themselves may be able to bring a particular kind of wisdom to the table that will be essential for our species-wide transformation. Indigenous societies have long recognized how important such voices are for the health of their communities; isn’t it time that contemporary societies rediscover the wisdom of this?

Anais Nin wrote a short poem that I think captures the essence of our dilemma while proposing a challenge that I think we need to seriously consider: “And then the day came when the risk it took to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.” So what will it be? Will we as a species continue to cling to our constricted selfhood until the bitter end, or will we find within us the wisdom and the courage to “blossom” and reclaim our membership within the broader living systems of which we are a part?

References

Johanson, G., & Kurtz, R. (1991). Grace unfolding: Psychotherapy in the spirit of the Tao-te Ching. New York: Bell Tower.

Mindell. A. (2008). City shadows: Psychological interventions in psychiatry. New York, NY: Routledge.

Perry, J.W. (1999). Trials of the visionary mind. State University of New York Press.

Prigogine, I., & Strengers, I. (1984). Order out of chaos: Man’s new dialogue with nature. New York: Bantam.

Williams, P. (2011). A multiple-case study exploring personal paradigm shifts throughout the psychotic process from onset to full recovery. (Doctoral dissertation, Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center, 2011). Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/34/54/3454336.html

Williams, P. (2012). Rethinking madness: Towards a paradigm shift in our understanding and treatment of psychosis. San Francisco: Sky’s Edge Publishing.