Written by Anastasia Basil / Human Parts

I don’t want to tell my kids what to eat — but maybe I should tell them why I’m vegetarian

My daughter and her best friend are in the kitchen rummaging through the cabinets. They find what they’re looking for: gummy bears.

“Those might be old,” I say.

We don’t care.

“Fine, but before you eat them I want you to watch this video.”

I’ve been meaning to show my daughter this video, but the timing never seemed right. When is it ever a good time to get stung in the eye? (“Now that everyone’s finished eating pie, can someone bring in the bee?”) I retrieve my phone and pull up the clip. Midway through, my daughter buries her head and cries. Her friend, motionless, stares at the floor.

My regret is instant and sharp. I am the worst mother ever.

I haven’t shown them anything particularly graphic: This is science; this is how gummy bears are made. The video shows dead pigs strung upside down on a factory conveyer belt. Their skin is being shaved with a butcher’s electric saw. The pigs face an incinerator and begin to melt near the inferno — then the camera cuts away. Surely two sixth graders have seen animals roasted before. There’s a Greek restaurant we frequent where gyro spins on a spit, bacon sizzles on the grill, raw meat is seasoned and mashed into patties. This is dinner. This is life.

I reason with my panicked self: All I’ve done is draw the curtain. I’ve taken them behind the scenes, shown them the props and the prop masters — where the magic happens. I didn’t find the video on the dark web; it’s from a popular Belgian show called Over Eten about how our food is made. The show’s hosts are beautiful model-type people. HuffPost Parents shared the video on its Facebook page. It’s okay, I tell myself, this is hard, but it’s okay.

So why do I feel so bad? Why do I feel I’ve done something I want to undo? Kids her age play Fortnite — the first-person shooter game where players entertain themselves by killing puppies with guns and axes. I’m sorry, did I say puppies? I meant people. (Puppies being shot in the head with an AR-15 wouldn’t fly. Parents would be outraged.) Plus, loads of her friends have access to YouTube, where videos of children being force-fed by their parents or urinated on by siblings abound. There are millions of “wacky” family videos masquerading as friendly content. YouTube identifies them as child-abuse fetish channels, but struggles to keep up with deleting them. Then there’s this guy: YouTuber Dick-Around Dylan, who wanders the streets asking girls and strangers sexually explicit questions and talking about how many b*tches he f****. His biggest fan base? Middle-schoolers.

Point being: I need to calm down. I haven’t shown my daughter and her friend anything morally questionable.

Have I?

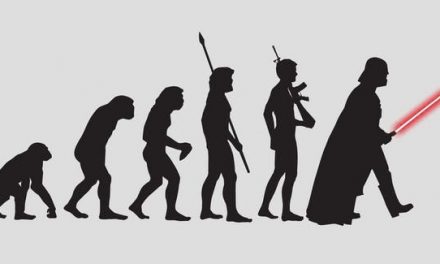

So much of who we are is decided for us: by genes, by nurture, by sheer luck.

I’ve got two kids crying in my kitchen; one is a vegetarian and the other loves bacon. My daughter doesn’t eat meat. She knows gelatin (a common candy ingredient) comes from animals but until now, she hadn’t pictured the how of it. I understand why my kid is upset… but her best friend? The lover of pepperoni and bacon? Surely, she knows the mechanics of her dinner. Surely, this is not a surprise. (For the record, my husband eats meat, and so does my youngest daughter.)

I do what any parent would in a panic: I give the kids candy and talk quickly while they chew. (Thank you, Skittles. Bless your pig-free rainbow.) I explain the power of choice. A Google search results in a list of gelatin-free options: Sour Patch Kids, Swedish Fish, Twizzlers.

Which brings me out of my kitchen and into the great wide world:

As parents, we aim to raise compassionate humans. No one gazes lovingly at their baby thinking: I hope he grows up to be hedonistic egoist. The question is, who, specifically, should be the recipient of that compassion? Is there a hierarchical order, and does it change over time or with location? Society’s behavior reflects the moral flux of its time. Slavery was legal, then it wasn’t. There were no laws in the U.S. protecting children from abusive parents. The first case against child abuse was brought forward, ironically, by the ASPCA in 1874 when it tried to save a little girl named Mary Ellen McCormack from her mother. The ASPCA hired a trial lawyer to argue that children are as much a part of the animal kingdom as horses and pets, and they too, deserve rescuing.

Hitler’s racial hierarchy reigned not so long ago. (Which wasn’t fully Hitler’s — German eugenics were influenced by American eugenics. I’m looking at you, California.) You had your Nordics at the top, your southern Europeans, and below that, your homosexuals, disabled, and otherwise genetically unfit. Beneath them were the Slavs, equatorial Africans, and at the bottom were Jews. Don’t forget the basement: That’s where the women are, all of them, Jew or not. As for war and its politics of death, the ranking is universal: Better their sons dead than ours. It makes sense that we extend this ranking system to animals. You’ve got your pups and kitties up top, and your Bessies and Wilburs at the bottom.

I’m often praised at barbecues: “You’re such a good mom for not forcing your views on your kids.” Meat-eaters look at me and like what they see: a vegetarian who “allows” her child to eat animals. “It’s great that you let her make her own decision about meat!” I nod and smile. Secretly, I imagine replying: I’m going to let my daughter poke your dog in the eye because I want her to make her own decision about animal suffering.

Never do we hear, “It’s Johnny’s choice if he wants to shoplift or steal from his friends, I’m not going to make that decision for him.”

As parents, do we not “force our views” on our children every day? You shall not punch, kick, or steal. You shall not hurt your (sister/ friend/ teacher/ birdy/ planet). You shall not take (Jesus/ Yahweh/ Allah/ Brahman/ Waheguru’s) name in vain. Childhood is a series of shall nots: partly because no one wants to raise a heartless narcissist, and partly due to random assignment of birth. Imagine souls comparing schedules before the first day of life:

What’d you get for religion? I got Catholic.

Darn, I got Zoroastrianism. Maybe we can still sit together at lunch?

So much of who we are is decided for us: by genes, by nurture, by sheer luck. So why, as a parent — as a nurturer — do I hesitate to decide this? Living ethically means striving to do the least harm possible, does it not? American children don’t need to eat animals for survival. It’s a choice, like chocolate or vanilla, paper or plastic.

Less than 2% of the American population works in agriculture, yet I allow my daughter to believe her bacon lived a happy life in a little red barn with a kindly farmer. That America existed once. (If you’re feeling nostalgic, you can visit it in the children’s picture book section at the library.) What’s real, now, are “downers.” Do you know what those are? They’re animals that have collapsed at meat factories and can’t get back up. They may or may not be ill; often they just need some water. In his book Eating Animals, author Jonathan Safran Foer explains, “In most of America’s fifty states it is perfectly legal (and perfectly common) to simply let downers die of exposure over days, or toss them, live, into dumpsters.” He tells the story of driving through Lancaster stockyards and seeing a pile of downers. One sheep in the pile lifts her head. He puts her in the back of his van and drives to a vet expecting she’ll be euthanized. After a bit of prodding, up she stands — raring to go. He takes her home to his family and she lives 10 more years. (Anyone want to illustrate that children’s book? Pile of dead animals, one lifts its head and… smiles?)

As a parent, I ask: Does my youngest, my meat-eater, have a right to know about “downers”? And how will this information change her choices, and fundamentally, her humanity? Quietly, I worry: What if she responds with indifference? What if her committee of Me, Myself, and I rejects the evidence?

Oxford historian Yuval Harari Noah believes if we really understand how an action causes unnecessary suffering to ourselves or to others, we’ll naturally abstain from it. His book 21 Lessons for the 21st Century offers a range of mind-expanding observations:

The meat industry not only inflicts untold misery on billions of sentient beings but is also one of the chief causes of global warming, one of the main consumers of antibiotics and poison, and one of the foremost polluters of air, land, and water.

Why then, do we not change our behavior? Harari says it’s because we don’t truly grasp the misery we’re causing. We’re fixated on satisfying our immediate need.

This is heavy stuff for me. What if my youngest remains fixated on satisfying her immediate desire? All around her, people eat meat from animal factories — including her father. No one has put him in jail for it, and I still like him… so how wrong can it be?

None of us should ever stop caring about the difference between right and wrong.

We are, I think, midway across a bridge. In 1963 only 23% of Americans approved of the March on Washington, where MLK delivered his (now beloved) “I Have a Dream” speech. No one in 1963 envisioned a federal holiday commemorating his birth, disdained as he was. Not long ago, few predicted victory for marriage equality. Slowly, ever so slowly, Americans come to their senses. Where will we be 50 years from now when it comes to animal suffering?

What if I told you that biotechnology is currently being used to create real meat, grown from animal cells, all without raising and slaughtering entire creatures? Ann Veneman, the former executive director of UNICEF and former U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, recommends a book called Clean Meat. Many points raised by author Paul Shapiro gave me pause, especially this one:

Imagine walking through the poultry aisle of your local supermarket. For each chicken you see, envision more than one thousand single-gallon jugs of water sitting next to it. Then imagine systematically, one by one, twisting the cap off each jug and pouring them all down the drain. That’s about how much water it takes to bring a single chicken from shell to shelf. In other words, you’d save more water skipping one family chicken dinner than by skipping six months of showers.

This fact alone is enough to question whether we can, in good conscience, continue to feed the demands of our gastronomical gods.

If the idea of lab-grown “clean meat” seems unnatural or gross, have you watched raw footage from an animal factory? The entire thing, not just two seconds of it. I don’t recommend it, unless you’re interested in disbanding your committee of Me, Myself, and I. Once you see what happens, you’ll agree there is nothing natural about sustained suffering; in fact, it’s gross.

Corporate fat cats would rather you not focus on the hellish how of animal production, or that four industry titans produce 85% of all the beef in the United States. Animal cruelty is a byproduct of Big Agribusiness, which is why many states have Ag-Gag laws that prohibit filming inside the industry’s most sacred temples — factory farms. The irony is rich: Filming animal abuse will land you in jail.

We do not think ethically about everything. Your decision to wear grey socks rather than brown will not affect other living beings. But should we think ethically about animal suffering? Or is the topic morally neutral, like sock color? If so, is it okay if my kid pokes a dog repeatedly in the eye? Or a pig? Or a hen?

Loosely defined by Princeton professor of bioethics Peter Singer, the principle of equality goes like this: “If a being suffers, there can be no moral justification for refusing to take that suffering into consideration.” The principle of equality requires us to account for all suffering equally.

As if that weren’t heavy enough, Singer drops this bomb:

Racists violate the principle of equality by giving greater weight to the interests of members of their own race. Sexists violate the principle of equality by favoring the interests of their own sex. Speciesists allow the interests of their own species to override the greater interests of members of other species… the pattern is identical in each case.

Clearly, I’ve failed to teach my youngest the principle of equality. Your tummy is interested in pepperoni, the interest of your tummy shall be served. To hell with the suffering of animals that aren’t dogs! Dominos is offering a two-fer on Meat Lovers!

We teach kids to identify vegetables — this is a carrot, this is an onion. But with animal bodies, we mask the truth: we say ham, hotdog, steak, salami, burger. We do not say, “Finish eating the pig’s belly and then you can have dessert.” Parents work hard to dissociate meat from its animal origins because, given a choice, preschoolers won’t eat a dead animal — but they will eat “bacon” (whatever that is). There are no picture books that teach toddlers to identify animals by their carcass names. Eating a pig is easy, but knowing it got punched in the head before it died — is not so easy. Most parents won’t make it through this Rolling Stone article about animal factories. The truth is hard to stomach.

Still, I hesitate to “force” vegetarianism on my kids, though other parents “force” meat on theirs with little apprehension. Maybe I need to stop seeing it as vegetarianism. Maybe I need to see it as the principle of equality, which is an inarguable principle, however inconvenient it may be to the committee of Me, Myself, and I.

None of us should ever stop caring about the difference between right and wrong. Hopefully, Harari is right, and once we grasp the misery we’re causing — to any being — we’ll naturally want no part of it.