Written by Charles Eisenstein

My daughter-in-law Ember is a nurse and a midwife. After much training, a year or two ago she attended her first clinical birth as an observer and assistant. A young male obstetrician was in charge. A Latina woman who spoke no English was on the birthing table; she was nearing the end of labor and the contractions were rapid. Looking in the general direction of the mother, the obstetrician announced in a loud voice: “This labor isn’t going well. Your baby is at risk. We are going to have to use suction.” The woman didn’t understand a word he said, but Ember saw fear in her eyes. Ember thought there was no need whatsoever for suction or any other kind of intervention. As far as she could see, the labor was going fine. But she dared not speak out, because she knew she would be immediately thrown out of the room if she did.

Then Ember saw a strand of baby hair peaking through the birth canal. She knew that birth was imminent. The obstetrician obliviously set up the vacuum and prepared for suction. Ember knew there was not much time before woman and baby would be subjected to a traumatic, potentially dangerous, and wholly unnecessary procedure. Her eyes locked onto the eyes of the birthing mother. Silently, she transmitted to her: “Push! Do it now! You can do it, and now is the moment.” Eye to eye, she knew the woman understood. She focused all her energy on a push.

Before the obstetrician could apply the suction, a beautiful, healthy baby was born.

* * *

During their visit, my son Jimi asked me what I thought of the new Amazon series, The Rings of Power. Confession: I haven’t watched it. My impressions come from reviews, the trailers, and from what people such as Jimi have told me. Apparently the hero of the story is Galadriel, depicted as a beautiful elf warrior-woman, mighty with the sword.

This depiction of Galadriel both is, and is not, true to the original Tolkien character. Tolkien portrays her as extremely powerful, marveled at, feared and revered. It is she who maintains the ancient magical realm of Lothlorien, she who leveled Sauron’s second fortress of Dol Goldur. Yet there is no hint that she possesses any martial skill. Neither her power nor her status have anything to do with her ability to wield a sword. That is not how she defends her realm.

While war drives much of the drama in the Tolkien books and especially the film adaptations, it is not always force of arms that decides their great events. Sauron’s armies, for example, are an instrument and expression of his will; when the one ring is destroyed and Sauron perishes, his armies panic and flee, unable to fight. Their crushing advantage in numbers turns to dust. But the greatest power of all in the original Tolkien work is the power of song. In the mythology of The Silmarillion, a pantheon of major and minor deities sings the world into existence. The first dark lord, Morgoth, starts his rebellion against God by introducing discord into the melody. Thousands of years later, the heroic couple Beren and Luthien overcome him in what seems to be a battle of song: Luthien’s song puts him to sleep, whereupon Beren wrests a jewel from his iron crown. It is presumably by song that Galadriel levels Dol Goldur. Tom Bombadil uses song to free the hobbits from the evil Old Man Willow tree.

But I digress—I can’t help it, I am a bit of a Tolkien nerd. What I’m pointing to is a conception of power, of the ability to shape the world and alter destinies, whose primary source is not strong arms and sharp swords and what those represent. But here the filmmakers have translated her power into martial skill, or have at least decided that martial skill must be a key aspect of her power. They are not alone in doing this of course; it is much the same in superhero movies, military movies, and action movies of all kinds in which the plot resolution hinges on a contest of force.

Traditionally, the ass-kicking hero is a man. Female protagonists abound in folklore and literature, but rarely do they seek to overpower their antagonists. Only recently have female characters stepped into the roles that men once monopolized. Many see this as a victory for feminism, or a sign that the producer is in tune with progressive values. No longer is power for men only.

But is this really a victory for women? If we take for granted society’s current arrangement of power, money, status, and values, then yes. But one might also view it as a capitulation to patriarchy, in which women join the system that has oppressed them and adopt its values and its blindness.

Let me put it another way. First a distorted patriarchy demotes women to second-class status, holds feminine powers in irrelevancy and contempt, and ultimately denies them altogether. Then women internalize that attitude, demean their own femininity, doubt the worth of their feminine powers, take on the cultural blindness to feminine power generally, and replace it with masculine power in an attempt to become what Ursula K. Le Guin called an “honorary man.” Those who succeed earn the privileges and status once reserved exclusively for men. They become CEOs, commanders, engineers, judges, career women. Thus they earn status and financial reward, in contrast to their sisters who never achieved escape velocity and remain full time mothers or homemakers or low-paid, low-status members of the caring professions.

In today’s politically charged atmosphere I should hasten to add that I am not saying that women should not become CEOs and so forth. If I were to phrase anything in terms of “should,” I would say, rather, that when women do these things, it should not be because society values little else. It should not be because they are given little choice but to join the patriarchy. Women should be free, neither locked out of patriarchal roles nor pushed into them.

Back to Galadriel. Last night I did my duty and watched the first episode of The Rings of Power. Not bad, really. It confirmed my suspicions though. The heroic Galadriel is not only a mighty warrior, she also displays the necessary attributes of one. She is obsessively goal-oriented, she steels herself against her softer emotions, she pushes her team relentlessly, she masters her desire to return home. Always she wants to forge into new territory, pushing herself and her followers to their limits. By traditional standards, she is not feminine in any way beyond appearance.

Is this to be the model of the new woman? Is this progress for women’s equality? Again, taking our current system for granted, then yes. If traditional feminine roles and ways of being are devalued, then it is indeed progress for women to escape them.

It would be a much deeper feminism to revalue what patriarchy has devalued, and to center society around the feminine powers that have been restored. Restored, first to visibility, and then to reverence.

* * *

In the birthing room, the powers of both the birthing woman and my daughter-in-law were invisible to the presiding physician, who was eager to ride in to save the day with his strong arms and sharp sword. It is not that his drugs, his forceps, his suction machine, and his scalpel have no purpose. It is not that the bulldozer, the ax, the computer, the algorithm, the technology have no purpose. But who is to know when they are to be used? How are they to know? These questions are a gateway to the restoration of feminine powers and the restoration of matriarchy.

To be sure, the obstetrician, though a man, could have tapped into his own feminine powers. He would have inhabited a basic trust in the process of life. He would have listened and observed, deeply and attentively. He would have especially listened to and trusted the women present instead of taking charge and going it alone. The solo leader out in front is an aspect of patriarchy. It is not inherently bad. It is bad when it is celebrated out of proportion to other arrangements of human beings. It is bad when the solo leader out in front doesn’t know where to go but pretends he does.

Though the male obstetrician could have inhabited his feminine side, he did not, and normally it is women who have the most ready access to it. The core of feminine power is intimate connection to life. In that connection, Ember knew intuitively that no vacuum suction was needed. She knew the birthing woman could do it without intervention, just as she would also have known if intervention were needed.

Those disconnected from life can always find a reason to use the suction, the scalpel, the bomb, the excavator, the sword. What could make the elves with their swords different from the orcs with theirs? Only a difference in their knowledge of when to use them. When this knowledge is sourced from intimate connection to life, then matriarchy is operating.

Even if all the sword-wielders are men, when they take direction from feminine connection to life, they are still governed by a matriarchy. Matriarchy puts life at the center. I once heard someone claim that the Kogi are a patriarchal culture because it was a party of exclusively male Kogi that greeted a group of visitors at the border of their territory. If women were in charge, wouldn’t they be included in the party too? I said, how do you know what is going on behind the scenes? If you asked them, they might say, “The women sent us to the border. Of course we wouldn’t put the precious ones out in front.”

Do we recognize power when it doesn’t conform to patriarchal expectations?

Through the eyes of an imbalanced patriarchy, matriarchy is invisible. Matriarchy is not patriarchy with women substituted into men’s patriarchal roles. It is not women exercising the kind of power that men have in patriarchy. Matriarchy enacts another kind of power entirely, one that the modern mind cannot easily recognize. Currently we live in the terminal stage of a degenerate form of patriarchy. (Degenerate forms of matriarchy are also possible, but have not been seen on earth for a very long time.) There is also a true or sacred form of patriarchy, just as there is a true, sacred form of matriarchy. The latter does not replace the former. A healthy society is a marriage of matriarchy and patriarchy.

Feminine power does not move the world through force. It tethers the masculine powers to life, directs them toward love, and keeps them grounded in beauty. In the marriage of matriarchy and patriarchy, the masculine asks the feminine, “Where shall I direct my powers?” The untethered masculine runs awry, building towers of abstraction and technology that grow ever more distant from matter and life.

The province of matriarchy is what. The province of patriarchy is how. What shall we do, that is in service to life, love, and beauty? How shall we do it? These questions merge and flow into each other. What becomes how, how becomes what. Such is the conjugation of matriarchy and patriarchy.

The weaker the connection to life, the more it appears necessary to apply forceful intervention, and the more it seems that human progress consists in amplifying the techniques of force. The result has been endless struggle and alienation, as the world turns into an opponent and an object. Little does the alienated masculine suspect that far greater power, security, and ease is available through union with life rather than domination of it.

The late Japanese farmer-sage Masanobu Fukuoka transmits this in his book The One-Straw Revolution. As his attunement to the land deepened, he found he needed to do less and less, because he knew more and more clearly what he did and did not need to do. He went to the land after leaving a university agronomy department and the scientific knowledge he’d acquired there. Instead of principles of science, he looked to the land itself, with its soil, water, plants, and animals, for information. If there is a principle within Fukuoka’s philosophy, it is intimate relationship with land, deep listening, and trust. This was his connection to the feminine powers that enabled his masculine mode of intervention to serve life. That is what our masculine powers are for, you know. What else would they be for?

The ruin of matriarchy in modern civilization leaves the patriarchy adrift, unsure of where to direct its life force. An intact and thriving matriarchy would leave it no doubt. We could ask the circle of grandmothers, the women in the red tent, or whatever their mass-society equivalents might be for direction. In the same spirit, childbirth would center on deep trust in the organic wisdom of the mother and the midwives who have developed deep sensitivity to her. What today have become routine interventions would be rare. The heroic doctor would no longer “deliver” the baby after having usurped her primary power.

I realize, of course, that today many women feel safer in the hands of the medical profession and welcome the interventions and trust procedures prescribed based on statistical outcomes. It is not my role to tell women what to do. However, these choices might come from internalized patriarchy—a disconnection from the worth and power of the feminine. Which takes me back to Galadriel, in whom we see internalized patriarchy re-externalized. Is the worth of a woman to come from outdoing men at their own game?

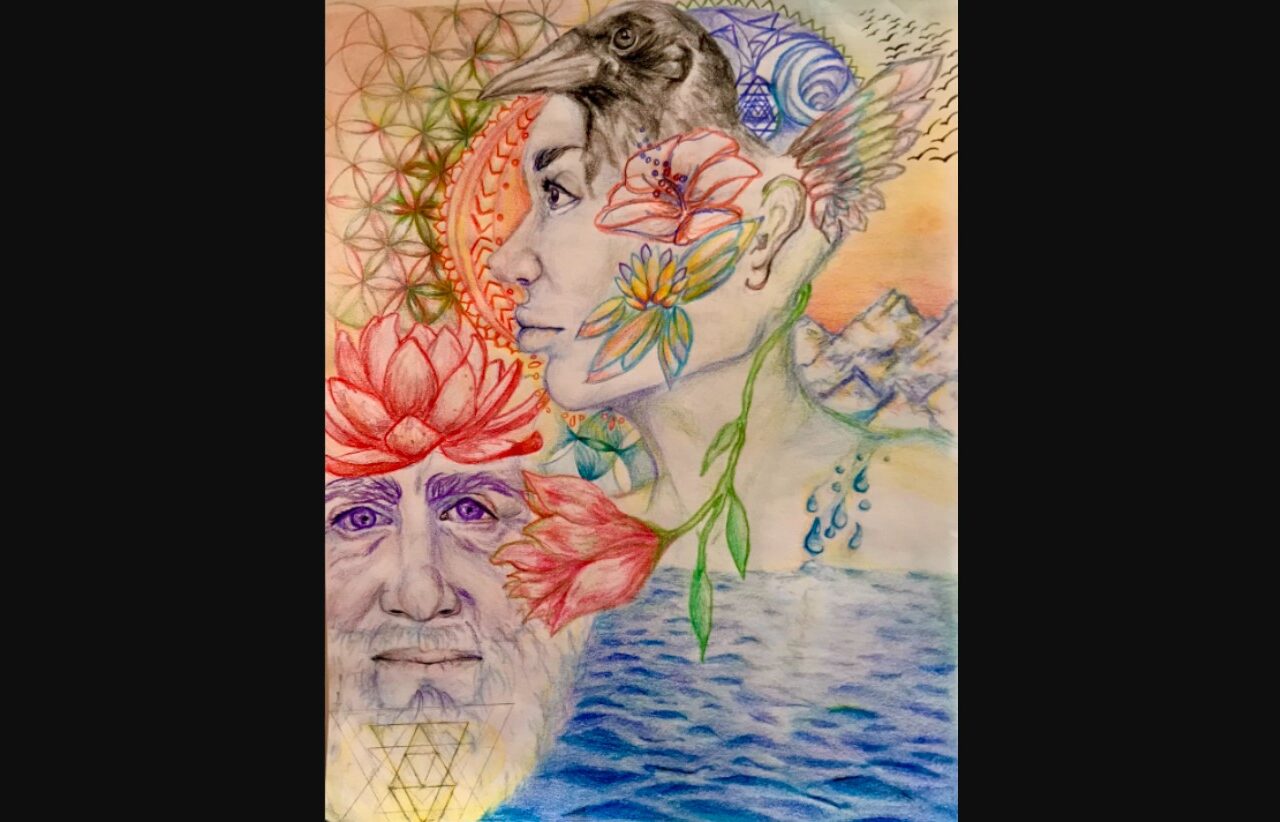

Up until the late 20th century, women were not even permitted to play the men’s game, and were excluded from vast areas of human endeavor. That was a great loss to women and society at large. But in validating their participation in science, politics, business, and so on, we risk demeaning those who make another choice. I know many women who have expressed to me their shame at being “only” a mother. I would like to see them celebrated too (and economically valued by society). I would like to see films that explore and ennoble female characters on a feminine path: not sexual accessories to men, and not honorary men, but fully inhabiting once-neglected and demeaned feminine archetypes. A film, say, about a wise old grandmother, and how the world can reorganize around her power. How does she sing good things into reality? An ambitious young man comes to her, having been humbled by seeing the harm his powers have wrought despite his good intentions.

That young man is civilization itself. It is time to seek the Grandmother.