Written by Isaac Yuen / Ekostories

It began with pronghorns. Growing up obsessed with creature comparisons, the main allure of the antelope was its cheetah-esque speed, evolved to evade the North American version of that predatory cat long extinct. I was tickled by the idea that the pronghorn outran its ghost and thus forever evaded its own doom. In these later years and slower-paced days, other commendable qualities came to the fore: Those long-lashed doe eyes; that sly, set hint of a smile; the pair of ebony horns sheathed in keratin which shed like antlers; the tinge of melancholy derived from knowing that it is the sole survivor of its family, the last remnant of kin.

It began with pronghorns. Growing up obsessed with creature comparisons, the main allure of the antelope was its cheetah-esque speed, evolved to evade the North American version of that predatory cat long extinct. I was tickled by the idea that the pronghorn outran its ghost and thus forever evaded its own doom. In these later years and slower-paced days, other commendable qualities came to the fore: Those long-lashed doe eyes; that sly, set hint of a smile; the pair of ebony horns sheathed in keratin which shed like antlers; the tinge of melancholy derived from knowing that it is the sole survivor of its family, the last remnant of kin.

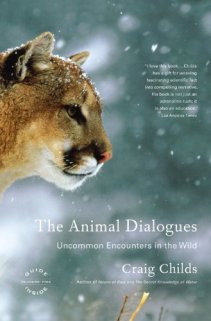

It was a fortuitous flip to the essay on pronghorns that persuaded me to pick up Craig Childs’ The Animal Dialogues: Uncommon Encounters in the Wild. In each intimately wrought tale on antelopes, hawks, and red-spotted toads, I found a writer and translator more versed in the tongues of the non-human world than I will ever be. Childs honors the weight and magnitude of his encounters with creatures large and small, preserving the distance and mystery that comes with each meeting. He strives to convey in words what cannot be expressed in words, and in each essay I see one who does what I wish to do myself: To connect with respect, to speak for the voiceless, to bear witness to life and death in their eternal splendor.

***

When I was in Primary One, the teacher handed out a worksheet that tasked us to group things as “animal”, “plant”, or “other.” It seemed like a simple enough task. With my black and yellow Staedler pencil, I quickly circled the cow and looped it to “ANIMAL”. Next, a straight line from carrot to “PLANT”. Then, a man with a bow tie. I chose “OTHER.”

“In his great poem on the Nature of Things, Lucretius saw no barrier between man and the rest of creation; he saw the nonhuman world as the matrix in which mankind is formed and nourished, to which we belong as the garnet belongs to the rock in which it crystallized, and to which we will return as the sunlit wave returns into the sea.”

– Cheek by Jowl, Ursula K. Le Guin

I still remember my surprise at being told that human beings were, in fact, animals. Since then, I have often wondered when and how my six-year old self learned to forge that divide and cleave the world into two. Was it a result of being born into a world of high-rises and concrete parks, where creature experiences came chiefly from books and cages and slabs of quartered meat? How different was my childhood compared with Childs’, who began The Animal Dialogues with his early account:

“I was very young when I woke before dawn and grabbed the small knapsack beside the bed. In it I placed a spiral notepad, a sharpened pencil, a paper bag containing breakfast, and a heavy thrift-store tape recorder with grossly oversized buttons. I walked outside, through the neighbourhood, and at the edge of a field full of red-winged blackbirds, I took out the tape recorder. Their officious prattle lifted like shouts from the stock market floor. I pushed record and listened.”

– The Animal Dialogues, p.1

Childs grasped the human-animal connection early. I learned it late. But not too late.

***

Things learned while reading: Female coyote biology allows them to shrug off attempts at population control. Porcupine spines contain antibiotic properties to help stave off infections from accidental self-stabbings. Eagles can spot salmon from five thousand feet up and dive down without a single course correction.

A peregrine falcon in flight. Image by Kevin Cole.

Yet these natural history details, deftly woven into each narrative, seemed never the chief thrust of Childs’ tales; science and facts supplement but do not supplant. The prose, steeped in metaphors and rendered with a poet’s sensibility, broach closer to the essence, but are in the end still words. What comes across and moves me most is Childs’ earnest impulse to negotiate with animals in their own domains, whether that be physical, deep down in the canyon depths of desert bighorns and up in the sculpting currents of bald eagles, or temporal, as creatures always anchored in the realm of the here and now. Shackled to our intellects, humans throughout history have envied animals for their ability to be at ease in the ever-present; the most poignant passages in The Animal Dialogues are when Childs grows urgent in his yearnings to cross over, to strive to feel what it is to be bear or falcon or smelt, now, before returning as a human being, humbled and awed:

“The peregrine floats in the air just beyond arm’s reach. It looks back at me with such equanimity, such singularity, that I am emptied, contentedly bankrupt. This must be what it feels like to fly for the first time, to actually open up and soar, exchanging gravity for faith.

… The low voice says that my time is over and it would be polite for me to back away. I do. I slowly step from the edge, returning to the earth, where I can no longer see the floating falcon or the cliff cascading below. The world around me folds back into its neat little boxes of dimensions and nearby distances. Broken red rocks appear at my feet. Once more I am an ordinary living man, no longer eolian, no more a creature of wind.”

– The Animal Dialogues, p.110

To be an animal is to be complete. To be enough. As humans we can only guess, dream, and wonder. We have to make do.

***

“For Isaac—Listen for coyotes, follow ravens. Be one of the animals.” Childs signs this in the top right-hand corner of my copy of the book. But being present and in the moment is not my natural state. Almost always my attention beats a retreat into the abstract, impatient for senses to register so that I can begin to dwell in possibility. But recalling the inscription, I try to heed Childs’ advice in my small way. Even in this city there are stories, if I would only notice.

After work one summer day, I sit on a bench at David Lam Park in Vancouver and look out at the inlet. A swallow scrawls cursive loops on a canvas too vast and blue for any one thing to fill. Ahead, a gull on a perch, tenses in the way I do when I am preparing to dive, except as it falls it pulls itself parallel to the sea instead of piercing it, leaving intact below the shimmering quilt of kelp and flotsam.

Before me, a city crow sporting a goatee of ruffled feathers charges the concrete pillars to scurry up beach hoppers. A great blue heron sails overhead like a pitched spear. I do not know how much time passes between each event, only that they come one after the other, invisible arcs and parabolas continuously being drawn and erased within this space, in all spaces. I sit and watch and write. Four Canadian geese and a raft of mallards follow the tide in to feed in patches of seagrass once landgrass. A child of five or six picnicking with her mother dips her plump toes into the sucking waves that break upon a sculpture upon which is inscribed “THE MOON CIRCLES THE EARTH AND THE OCEAN RESPONDS WITH THE RHYTHM OF THE TIDES.” I sit and watch and write, filling nine pages with moments. The present slips through my grasp like fine sand. But sometimes I am able to hold onto a few grains. Sometimes the words come out true.

***

My favorite essay in The Animal Dialogues is on violet-green swallows. It is the shortest essay in the book, rounding out at less than two pages of text, and reads like a breather between weightier pieces. It does not possess the stomach-clenching tension of a play-by-play encounter with a mountain lion, nor does it permeate with the sinister air of a mystery as Childs describes his intrusion upon a conspiracy of ravens. Unlike his story with the car-struck deer, it is not tender and heartbreaking enough to make Jane Goodall weep. There are no twists in this tale of violet-green swallows. Nothing much happens as Childs watches the birds fly as he swims in a pond.

It is my favorite because it touches upon something universal. It functions as an interlude, but an interlude that offers a glimpse into the world’s grand act, one of perpetual beauty, grace, and change. “The curve of a violet-green swallow is reminder enough to heed everything,” Childs writes, “to cinch down your life and your body like a harpsichord string and pluck it.” There is a purity to that statement I do not know what to do with. I have tried to keep it close, ever since.