Written by Alexandra Macmillan / The Conversation

Climate Explained is a collaboration between The Conversation, Stuff and the New Zealand Science Media Centre to answer your questions about climate change. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, please send it to climate.change@stuff.co.nz

Do you expect an increase in health issues due to the effects of climate change? – a question from Christine in Wellington

Some of the negative health effects of climate change are already upon us, but it’s not all doom and gloom. There is a huge opportunity for better health through well designed action to reduce our emissions and by adapting to the changes we are facing.

You may already be experiencing one of the potential impacts of climate change on our mental health. In recent years, the New Zealand Psychological Society has reported seeing some cases of anxiety, helplessness and depression about climate change. This is most evident when individual concerns are expressed collectively in the form of protest such as the school strikes for climate. Thousands of young people around New Zealand – and reportedly more than a million globally – have been striking to express their fears about the future.

The grief and depression that can result from the destruction of places and landscapes people love led Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht to create a new word: “solastalgia”.

Global warnings

In New Zealand, the past half century has seen ongoing improvements in the health of the overall population, with an expectation that our children will have better health, life expectancy and quality of life than their parents.

But as a number of reports have found, including medical journal The Lancet’s Countdown 2018 report, climate change may well undo these health gains in tandem with other ecological pressures we have created. Global measures of health mask unequal gains between populations and groups between and within countries. Climate change will make these health inequalities worse.

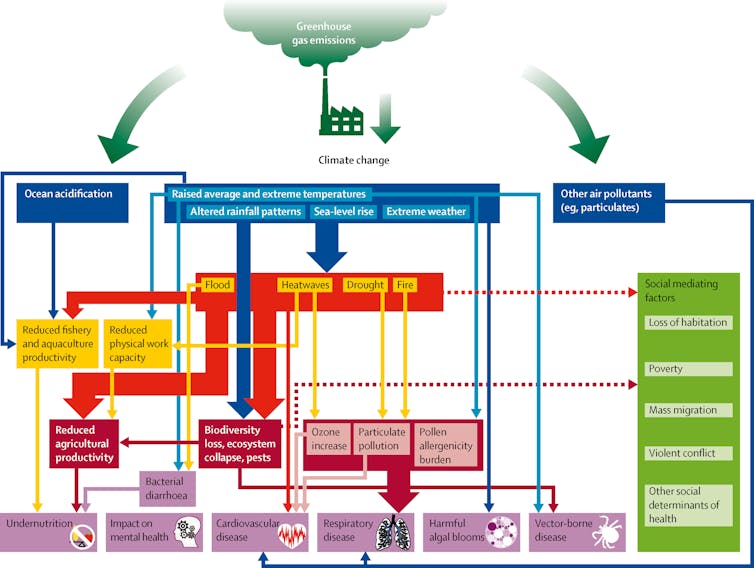

The pathways between climate change and human health, from a global report on climate change and health. 2018 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change, CC BY-NC-ND

The Lancet’s report warns that “the nature and scale of the response to climate change will be the determining factor in shaping the health of nations for centuries to come”.

Climate change and health in New Zealand

In New Zealand, warmer winters may reduce the number of people who die (currently about 1600 each year), mostly from heart and lung disease. But unfortunately, the overall impact will be negative on a wide range of other causes of illness and mortality. It is likely that climate change will bring diseases unfamiliar in New Zealand (especially infectious diseases, such as dengue fever), but more importantly, climate change amplifies chronic and infectious diseases we already suffer from, such as the impacts of heat on heart disease, and changing rainfall patterns on waterborne illnesses.

One major direct impact on health was made evident by the huge outbreak of campylobacter, a bacterial infection that causes gastroenteritis, in Havelock North during the winter of 2016. Some 5,500 people in a town of 14,000 residents became unwell, with 45 people hospitalised. A government inquiry attributed the outbreak to a combination of extreme rainfall that washed sheep faeces into a pond near a water bore and poor drinking water management. The outbreak may even have contributed to three people’s deaths.

Warming of freshwater and more extreme rainfall events are both part of climate change, increasing the likelihood of outbreaks like the one in Havelock North.

Indirect effects on health will be as important, but they are more difficult to measure and predict. Climate change undermines many of the building blocks of good health: clean air, plentiful safe drinking water, affordable healthy food, affordable dry houses, and economic stability and peace. The threat to food security and therefore nutrition is just one worrying example.

Changing seasonal temperatures and weather extremes are already reducing harvests of important staples like wheat, while warming oceans are reducing our ability to harvest fish and shellfish. Both are staples in New Zealand’s diet. We already have a problem with many families not being able to afford to always put a meal on the table, let alone a healthy one. When this worsens, the result is, perversely, an increase in obesity and diabetes, accompanied by nutrient deficiencies, as families rely on cheap, highly processed foods to get by.

Overall, many New Zealanders are experiencing better health than in the past, but we have persistent health inequalities as a result of multiple structural injustices, including poverty. People on low incomes, Māori and Pasifika, the elderly and children will be worst affected by climate change, but wealth and white privilege do not confer immunity.

The overwhelmingly negative effects of climate change on health are a strong argument for urgent action to reduce our climate pollution.

But well designed action also offers opportunities to address New Zealand’s biggest causes of death and disease: cancer, heart disease, diabetes and obesity. For example, if we reduce our transport emissions by improving access to safe walking and cycling routes and electric public transport, air quality will improve and we build physical exercise back into our daily lives. Shifting our farming sector from a heavy focus on producing milk powder towards plant-based food production would not only change our national diets for the better, but also ensure we are resilient to global food price shocks and improve our fresh and drinking water.

Our health system will need significant strengthening if we are to be in a good position to weather the coming climate disruptions. This is particularly so in public health, which sets up systems for dealing with outbreaks and emergencies. We also know from our experiences of past major calamities such as earthquakes, that the resilience that comes from strong communities is a huge advantage. Taking co-ordinated action together can be crucial for health during upheaval.