Written by Mari Margil / Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund

When Dr. Seuss’s Lorax sees the Truffula trees being destroyed, he declares: “I speak for the trees. I speak for the trees, for the trees have no tongues.”

No tongues, indeed. But today, trees are gaining a voice, and nature is speaking for itself and defending its own rights to exist and thrive.

For far too long, nature has been treated as something apart from us, without a voice, unable to say “no!” when threatened. And the consequences are all too real — from the collapse of ecosystems such as coral reefs, to the accelerating rate of species extinction, and of course, with climate change.

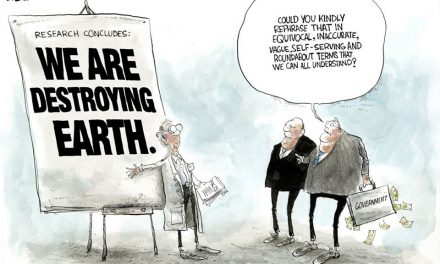

Many are asking, why, when we have so many environmental laws in place around the world, does it seem we are unable to protect nature?

Put simply, environmental laws are largely written to authorize the use of the environment. That is, environmental laws legalize activities that use water (such as fracking, which contaminates millions of gallons of water at each frack well), use the air (such as industries that are allowed to emit billions of tons of pollution, including global warming emissions), use land (such as industrial agriculture, which spreads insect-killing pesticides across billions of acres across the globe), and use species (such as industrial-scale fisheries, which are pushing species to the brink).

This legalized use of the environment has treated nature as infinite, able to provide for endless growth and development.

But nature is not infinite, and the consequence of this system of law has proven destructive of ecosystems, species, and biodiversity.

Today, we know that species extinction rates are occurring 1,000 times faster than natural background rates, which prompted the United Nations to warn that a sixth mass species extinction is in the cards.

Indeed, as the Earth Day Network explains in its Protect our Species campaign, the theme of this year’s Earth Day: “If we do not act now, extinction may be humanity’s most enduring legacy.”

Our actions are ripping holes in the very fabric of life.This will only change with a fundamental shift in humankind’s relationship with the natural world. Fortunately, that shift is beginning to happen.

Today, a new movement is building, which recognizes that we can no longer treat nature as limitless, or as simply existing for human use. This movement is transforming how the law treats nature — from being considered an item of property or commerce, to being recognized with legal rights of its own. This movement — to secure legal rights of nature — means, for the first time, acknowledging that nature has the right to exist, the right to thrive, the right to regenerate, evolve, and be restored. And, importantly, that nature can defend and enforce these rights against threats.

Past people’s movements have sought to transform those treated as right-less to being right-bearing, including movements for the abolition of slavery and for women’s suffrage. Much like those prior movements, the movement to recognize the right of nature represents a shift in the purpose of law and governance, from one of legalized destruction, to one of protection.

The rights of nature were first secured in law in communities in the United States, beginning in 2006. Two years later, Ecuador became the first country to enshrine the rights of nature — or Pacha Mama — in its national constitution.

Today, there are rights of nature laws and court decisions in India, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, and other countries. Tribal nations have enacted such laws, and more than three dozen communities across the U.S. have done so as well.

This transformation is occurring with the growing understanding that it’s time for change. Colombia’s Constitutional Court stated, in its 2016 decision recognizing legal rights of the Atrato River, that such a transformation in the law is necessary before “it’s too late.”

Today, people all over the world are mobilizing for change.

This includes action in Australia, where a campaign was launched last year to recognize rights of the Great Barrier Reef, which is home to millions of marine species. We’re seeing progress in the U.S., where the White Earth band of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe recently recognized legal rights of the very first plant species, manoomin (wild rice). We are also seeing movement in India, where the High Court of Uttarakhand declared legal rights of the “entire animal kingdom.”

The Lorax warned:

“UNLESS someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

Together we can make change.

To learn more about the rights of nature and how you can get involved, visit www.celdf.org or contact rightsofnature@celdf.org.