Written by Paul Kingsnorth / The Abbey of Misrule

This is the third and final part of Paul Kingsnorth’s three-part series on the virus and the Machine. Here are Part 1 and Part 2. Each part can be read individually (i.e., they don’t need to be read in order).

Everybody knows that the plague is coming

Everybody knows that it’s moving fast

Everybody knows that the naked man and woman

Are just a shining artifact of the past

Everybody knows the scene is dead

But there’s gonna be a meter on your bed

That will disclose

What everybody knows– Leonard Cohen, 1988

When is a conspiracy theory not a conspiracy theory? The answer to this question has a bearing on the shape of the coming world.

In this covidian miniseries, I’ve been writing about the stories we tell about the pandemic. In the first essay, I explained why I had grown to disbelieve much of the official story – what I called the Narrative – about the virus and the response to it. For me, the straws that broke the back of this story were the Austrian lockdown of the ‘unvaxxed’, and the Australian quarantine camps: after this, I couldn’t tell myself that what was going on was anything to do with any sane definition of ‘public health’.

Maybe I was slow to get there, but I was only one of many who reached the same conclusion. This last month seems to have marked a tipping point, as resistance continues to grow to what is happening, and hundreds of thousands of people take to the streets across the world, from Turin to Paris, London to Vienna, Melbourne to Barcelona, Christchurch to Tblisi. Mandates, passports, segregation, quarantine camps, censorship, the chilling demonisation of the ‘unvaxxed’: all of this seems to have brought a new clarity about the unprecedented territory into which we are headed.

In the second instalment, I tried to dig into why so many of us see this situation so differently: why those mandates and passports, for example, are seen by some as a necessary health measure which it is irresponsible to refuse, and by others as the beginning of a tyranny which must be resisted. I looked at how the stories we tell about the world determine our responses to the corona moment, and how these stories can divide us against each other, even as we all aim for our own version of a healthier society.

This time around, I want to look at the story the Machine is telling us about these times. I want to look at the world we are being rapidly steered into, as covid-19 becomes a kind of techno-political sandbox: a testing-ground for new ways of being human in an increasingly post-human world.

Stories are the means by which we navigate reality, but they are also the means by which we control it – and by which we are controlled. Control the story, control the population: this has been understood since the Pharaohs, and it is why the narrative battle over covid has been so fierce. It is why the media and the social media companies have worked so hard to shut down difficult questions about the vaccines, and why constant efforts have been made to silence, intimidate or bully people who are said to be spreading ‘misinformation’. And it is also why we have seen a new focus on a very different kind of storyteller, one previously mocked but now increasingly looked upon with both nervousness and wrath: the ‘conspiracy theorist.’

Once upon a time, not so long ago, we knew what a ‘conspiracy theorist’ was. It was somebody who offered up an outsider take – often a very weird one – on an official version of a well-known story. Sometimes the take was convincing (JFK wasn’t shot by a lone gunman), sometimes it wasn’t (the UN wants to kill 95% of the world’s population), and sometimes it was downright poisonous (the Jews are behind it all.) But we all knew that a ‘conspiracy theory’ was a story that pointed towards dark, hidden forces operating in the world: a story that said, something is being hidden, and should be exposed.

Of course, the phrase was something else, too: a smear. The ‘conspiracy theorist’ (who probably wore a ‘tinfoil hat’) was basically unhinged: not like us good and sensible people who obtain our information from TV news, peer-reviewed science and books featured in broadsheet newspapers. Still, these people were mostly harmless – and more importantly, they were irrelevant. People who obsess over the Roswell Incident or the faking of the moon landings are no threat to power, so they are ignored by it. In normal times, ‘conspiracy theorists’ simply don’t matter.

But what about the abnormal times? Times like this one, when trust in official sources of authority is cratering, when the narratives are fractured, and when more and more people are grasping in the fog for new maps? In times like this, three things happen. Firstly, a lot of new conspiracy theories proliferate, like flowers in long-dry soil newly opened by rain. Secondly, the phrase ‘conspiracy theorist’ becomes a useful tool for those trying to hold the official line: a term of dismissal that can be applied to any and all who question the Narrative, no matter how reasonable their questions might be.

Thirdly, some of those theories will turn out to be right.

It’s fair to say that the ‘conspiracy theorists’ have had a good pandemic. I can still remember a glorious headline from a well-known publication which appeared in early 2020, and hasn’t aged well: “Anti-vaxx conspiracy theorists are suggesting that covid-19 will lead to the introduction of ‘vaccine passports.’” There have been countless articles like this over the last eighteen months in numerous outlets, dismissing predictions of everything from passports to mandates to quarantine camps as crazy tinfoil-hattishness. This has only served to underline the craven and unprecedented manner in which much of the media has been behaving, as well as the shredding of their remaining credibility. But that’s another story.

Perhaps the most reported-on ‘conspiracy theory’ of the past year, though, has been that of the ‘Great Reset’. In this lurid tale – so we are told by those same media outlets – globalist evil genius Klaus Schwab, who lives under a volcano in Davos, plans to kill off 95% of the population (again), and take control of the world’s resources. The 5% of us who remain will own nothing but be happy, because there is no longer any climate change and we are all fully vaccinated and boosted and entirely onboard with whatever Klaus and Bill Gates have planned for us next, which will probably involve robots.

It’s true that there are various, shall we say, creative tales doing the rounds about Schwab and the agenda of his World Economic Forum (WEF). But the Great Reset itself is no invention of the paranoid, and neither is it a conspiracy. You could call it a plan, or an agenda, but it is best understood as another story: one that Schwab and his colleagues would like us all to adopt as our map for the coming territory. If you want to understand the simultaneously boring and sinister nature of this story, you don’t need to penetrate the deepest recesses of the mountain redoubt in which it was secretly hatched: you can just watch the online lectures, attend the virtual conferences, or browse the relevant section of the WEF’s website. Or, if you’re really keen, you can do what I did last week, and read Klaus Schwab’s book on the subject.

Covid-19: The Great Reset is disappointingly free of mind control devices, microchips-in-vaccines and reptilian overlords. It is, in fact, almost entirely free of anything interesting at all. It is a standard-issue globalist manifesto, of the kind that could have been put out by any editorial functionary at the WEF, WTO, G8, UN, World Bank or IMF, or any writer for the Economist or Forbes, in any year after 1990. When I was writing my first book, One No, Many Yeses, back in the early 2000s, I read dozens of books and papers like this, in an attempt to understand what drove the promoters of economic and cultural globalisation. They were – and are – always the same: a hymn to the saving grace of global capitalism, dressed up in social justice clichés and aspirational NGO-speak. Diversity, vibrancy, equality, inclusivity, poverty alleviation, motherhood, apple pie: since they first started falling victim to mobs of activists outside their conference centres in the late nineties, the captains of the Black Ships of global capitalism have been careful to disguise their piratical raids as charity projects, powered by a Lennonist desire for universal oneness.

Schwab’s book, then, has to be read on two levels. On the surface, his argument is bland, unsurprising and deliberately hard to disagree with. He says that the pandemic has changed everything, and that the world will never return to what it was. He also argues that ‘what it was’ wasn’t working in any case. The global economy (the one he helped to build) is changing the climate, causing inequalities in and between nations and giving rise to other contemporary bad things, from racism to ocean pollution. We should thus ‘seize the opportunity’ that the virus has conveniently brought about to ‘reset’ the world: to rebuild it in a fairer, better, and more sustainable shape.

So far, so agreeable. Who could object to less poverty and cleaner seas? You have to dig below the surface to understand what any of this actually entails – and, more to the point, how it is to be achieved. And you don’t have to dig very far to see the story beneath the story.

The covid event, explains Schwab, has shown that ‘we live in a world in which no-one is really in charge.’ For plenty of us, this might sound like a good thing, but for globalist thinkers like Schwab it is a problem to be solved. ‘There cannot be a lasting recovery without a global strategic framework of governance’, he writes. Nation states and their kindly allies in the ‘global business community’ must unite to ‘build back better’ (you may have heard this somewhere before). What does this mean? It means that there is no going back.

Schwab is clear that the measures taken to tackle covid – lockdowns, vaccine passports and mandates, medical segregation, mass sackings, widespread destruction of small businesses, the deepening of the profit and reach of Big Tech, and a radical normalisation of digital monitoring, surveillance and state control – have wrought permanent changes on our societies which will not be going away. ‘What was until recently unthinkable’, he writes, ‘suddenly became possible’. This is especially true when we look at the real winner of the covid years: the technological system itself.

While ‘some of the old habits will certainly return’ after the pandemic ends, writes Schwab, ‘many of the tech behaviours that we were forced to adopt during confinement will through familiarity become more natural.’ Home working, digital monitoring of employees by their companies, Zoom meetings and e-deliveries, not to mention the whole structure of the QR-coded ‘vaccine passport’ system: much of this is likely to remain in the new normal that covid has created. In the reset future, we will reconsider things which once would have been second-nature: things like spending time with our loved ones. Why, asks Schwab, would we endure ‘driving to a distant family gathering for the weekend’ when ‘the WhatsApp family group’ (though admittedly ‘not as fun’) is nevertheless ‘safer, cheaper and greener’? Why indeed?

This is the essence of the Great Reset: the construction of a future which is at once controlled and catatonic, dystopian and dull, monitored and monotonous beyond bearing. A future in which global corporations are free to build the world they have long desired: a borderless, interconnected market technocracy, in which each human individual is a tracked, traced and monitored production and consumption machine – all in the name of public health and safety.

Interestingly, Schwab openly observes, in a claim which might land anyone else a Youtube ban, that covid is ‘one of the least deadly pandemics the world has experienced over the last 2000 years’ and that ‘the consequences … in terms of health and mortality will be mild.’ The really lasting consequences, he writes, will not be wrought by the virus itself, but by the response to it. This culminates in the only striking image in the book, which Schwab uses to illustrate how the fear of sickness will linger long after any threat of covid itself has receded, and what this might lead to:

A new obsession with cleanliness will particularly entail the creation of new forms of packaging. We will be encouraged not to touch the products we buy. Simple pleasures like smelling a melon or squeezing a fruit will be frowned upon and may even become a thing of the past.

A smooth, clean, ordered world, free of dangerous melons on little market stalls, free of small businesses and anarchic commercial arrangements and awkward human interactions of any sort – a world run by efficient, clean, digitised corporations offering ‘e-solutions’ for any activity that might threaten our safety and wellbeing: this has been on offer for years now, but the pandemic – as Schwab openly acknowledges – has been a blessing for those behind it. We are prepared to accept things now which would have been inconceivable three years ago. What will be conceived next year? And who will listen to the ragtag mob of conspiracy theorists, anti-vaxxers, fascists and nutters who want us to say no to it?

This is the sort of thing that fuels the genuinely weird ‘conspiracy theories’ around Schwab and his agenda. But it’s not necessary to believe that the virus was deliberately released or doesn’t exist, to simply observe the wider picture. For decades now, nation states and their political leaders have been progressively disempowered by globalisation, and power has been concentrated in the hands of those who create and control the world’s technological infrastructure. Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Klaus Schwab, Jeff Bezos, Sergey Brin, Ray Kurzweil and the like have been moulding our reality for decades, and the limbic capitalism they pioneered has been hyper-charged by covid – as has awareness of it, and a growing counter-reaction.

We are living through a time in which the conflict between technocracy and democracy has spilled out into the open: the battle is being fought daily now on street and screen. Schwab has caught the spotlight because he is publicly attempting to put a storytelling framework around this conflict. Only last month, at a conference in (where else?) Dubai, he made this ambition explicit by rebranding his Great Reset as the ‘Great Narrative’. The world needed a new global story to unite it, he said. He and the WEF would help to ‘imagine the future, design the future, and then execute the future.’

Klaus Schwab planning to ‘execute the future’ is exactly the kind of thing that gets Alex Jones salivating. But though Schwab and the WEF’s power and influence should not be underplayed, he is not pulling the strings. There are no strings: there is only the Machine, and its direction of travel is long-set. Covid has provided the perfect testing ground and launchpad for a next generation of digital surveillance-and-control technologies which have been on the drawing board for years. The confusion, anger and division swirling around us all right now is a result of our confused inability to navigate the techno-coup we are living through, or even to quite understand what is happening.

But the future is off the drawing board now. Take those QR-enabled vaccine passports, which have been rolled out so rapidly all over the world over the last twelve months. They make little sense from a ‘public health’ perspective, since we know that the currently available vaccines don’t prevent transmission of the virus. But they do have the effect of normalising the technologies involved: technologies which were in the pipeline anyway. Digital vaccine passports have been in preparation in the European Union, for instance, since at 2018. In late 2019, months before the pandemic began, trials of ‘digital identity systems’ linked to vaccination status began in Bangladesh. It was hoped that they would demonstrate how to ‘leverage immunization as an opportunity to establish digital identity’ on a worldwide scale.

Again: no outlandish claims are required to make sense of this. It is simply an acceleration of the existing direction of travel. Most of us already carry around in our pockets a portable tracking device, which monitors our geographical location, harvests data on everything from our political views to our shopping preferences, and can be used by the State in extremis to determine who our friends and contacts are. It’s called a smartphone. As covid becomes endemic over the next year or two, and as new variants keep popping up, there will likely be continuing pressure for permanent guarantees of health and safety. Handily, we may be able to use those smartphones, already apped-up with our covid QR codes, as permanent ‘health passports’, which will allow us to access goods and services safely and digitally in the dangerous new world – whilst penalising or excluding anyone who refuses to avail of the recommended public health measures.

If this sounds like one of those nutty old conspiracy theories, bear in mind that actual passports – the ones we use to go on holiday – were themselves introduced as a temporary measure after World War One. The later justification for making them permanent on a global scale was ‘considerations of health or national security’ provoked by the Spanish Flu outbreak of 1918. A century on, the digital version is close to fruition, and the pandemic provides the perfect opportunity for its rollout. The WHO is currently negotiating with nation states, regional blocs and corporations to agree on the standards for global harmonisation of digital passports:

New tools developed as part of WHO efforts are almost ready. By the end of 2021, the DDCC Gateway (PKI) beta reference software is expected and a Universal Status Checking app beta, using Google Android FHIR SDK and based on the EU DCC … It is intended to be able to recognize all the health pass QR code formats being used worldwide.

So we will have have our permanent, global health passports, and they will then merge with already-existing digital ID technologies and the rollout of digital currency, to create for us all a personalised digital identity wallet which will be presented as an optional convenience but will soon enough become a basic requirement for taking part in the life of society, just as smartphones, credit cards and paper passports have. If you want to experience this future for yourself, you can watch this short film, made especially for you by one of the companies which is pioneering it. Doesn’t it look appealing? Safe? Frictionless? Speaking for myself, I’m feeling tremendously empowered already:

Once we have accepted the premise that deep and ubiquitous levels of surveillance, monitoring and control are a price worth paying for safety – and we seem to have done that already – then almost anything is possible. South Korea has just introduced mass facial recognition technologies in order to ‘speed up notifications of potential exposure to COVID-19.’ China famously operates a social credit system through which citizens are rewarded or penalised for their behaviour in multiple spheres. Media outlets are producing slick little films detailing how your covid passport could be conveniently stored on a microchip embedded in your skin. In the US, the FDA has already approved pills implanted with ‘digital ingestion tracking systems’, which send a signal to a smartphone when the medicine is taken. Perhaps you will be able to pay for them with your biometric cash card, imprinted with your fingerprint data.

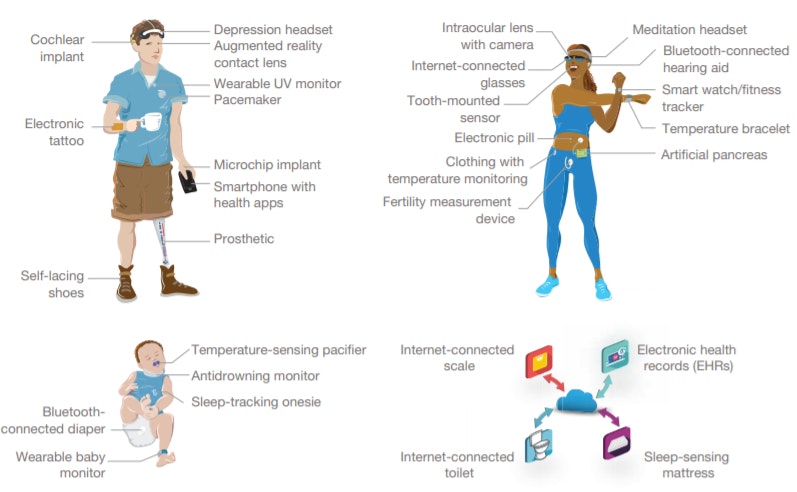

Buckle up: these are the coming times, and they are herding us directly and deliberately towards the main target: the ‘Internet of Bodies’, in which we begin to merge, finally, with the machines we have made. Microchip brain implants – ‘human enhacements’ which will allow us to ‘interface’ directly with the web – will be with us sooner than we think: their development is currently being funded by, among others, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg. The Royal Society, Britain’s premier league scientific thinktank, can’t contain its excitement about the possibilities they will offer:

Linking human brains to computers using the power of artificial intelligence could enable people to merge the decision-making capacity and emotional intelligence of humans with the big data processing power of computers, creating a new and collaborative form of intelligence. People could become telepathic to some degree, able to converse not only without speaking but without words—through access to each others’ thoughts at a conceptual level. Not only thoughts, but experiences, could be communicated from brain to brain …

In this story – the story of the Machine – the whole world, and everyone and everything in it, becomes a node in the glowing web that will make and direct our every waking hour. This future has, of course, been long anticipated. William Morris saw it coming, and so did William Blake. Aldous Huxley and E. M. Forster had its number a century ago, and Edward Abbey predicted it before I was born:

Call it the Anthill State, the Beehive Society, a technocratic despotism — perhaps benevolent, perhaps not, but in either case the enemy of personal liberty, family independence, and community sovereignty, shutting off for a long time to come the freedom to choose among alternate ways of living. The domination of nature made possible by misapplied science leads to the domination of people; to a dreary and totalitarian uniformity.

Covid has both accelerated and justified our dive into the digital anthill, and in coming years it will become more and more relentless. Perhaps many, even most, of us will welcome it. After all, it has been advertised at us for years, in the most deliberate, manipulative mass assault on our wills in human history. We have been trained to love – or at least accept – our smartphones, satnavs, Smart fridges, drones and Alexas. Luddites like me have always been a fringe sect. Certainly the people selected by the WEF as ‘young global leaders’ of tomorrow are excited by the future that they are being groomed to build:

When AI and robots took over so much of our work, we suddenly had time to eat well, sleep well and spend time with other people. The concept of rush hour makes no sense anymore, since the work that we do can be done at any time. I don’t really know if I would call it work anymore. It is more like thinking-time, creation-time and development-time.

Although, of course, every society has its downsides:

Once in a while I get annoyed about the fact that I have no real privacy. Nowhere I can go and not be registered. I know that, somewhere, everything I do, think and dream of is recorded. I just hope that nobody will use it against me.

This is not satire; this is prophecy. Or maybe it’s just marketing. Whichever it is, we have come at long last to the foothills of the future: an inverted version of The Matrix in which Agent Smith is the hero. A world both terrible and boring at the same time. As climate change bites, ecosystems continue to degrade, supply chains jam up, the social fabric frays, and mass urbanisation and mass migrations accelerate, it will become more and more necessary to micromanage, nudge and control the citizens of our mass societes just to keep the growth-&-progress show on the road. The pandemic has shown us how this can be achieved. Schwab is right that there is no turning back from the lessons it has taught.

Sometimes I think that what is happening now has no precedent in human history. At other times, it seems like human history as usual, only faster. When did we start augmenting ourselves, after all? When we invented glasses, shoes, armour, chipped flint? If this is what humans do, and what we are – animals who invent ourselves stronger, think worlds into being and then try to build them – is there any way to halt the march towards the merger of man and machine? Or did that already happen?

I could go on – I have gone on for years now. But it’s Christmas week, and I don’t want to end on this note. I want to end instead by saying something else: something I may not have expected to say at the beginning. But then that first essay, from a month ago, already seems like it was written in another time, so fast is everything shifting.

Here’s the thing: for some reason, despite all I have written about in this little trilogy, despite the coming winter, despite the new partial lockdown that my vaxxed-and-passported country has just entered, despite everything that the future seems to hold: despite it all, I feel some strange glimmer of hope. Control: this is the story that the Machine tells about itself, and it is the story that we would all, at some level, like to be true. But control systems never last. The world is beyond both our understanding and our control, and so, in the end, are people. We barely understand ourselves. Perhaps Klaus Schwab’s desire to ‘improve the world’ is real and felt: but he will still never be able to grip it tightly enough to bend it to his will. Who can?

The world is not a mechanism: it is a mystery, one that we participate in daily. When we try to redesign it like a global CEO, or explain it like an essayist, we are going to fail: weakly or gloriously, but fail we shall. The Machine, the technium, the metaverse: whatever we name our 21st century Babel, and however overwhelming it seems to us in the moment, it can never conquer in the end, because it is a manifestation of human will and not the will of God. If you don’t believe in the will of God, call it the law of nature instead: either way, it speaks the same thing to us. It says, gently or firmly: you are not in charge.

I can’t pretend to understand all of this. All I have is my intuition, and these words. But I think that the world is more surprising, and more alive, than I sometimes see or even want to believe. I think that the corona moment highlights an ancient ongoing struggle, between the spirit of the wild and the spirit of the Machine, and that this struggle goes on inside us all every minute of the day. Sometimes, battles must be fought, stands taken, lines drawn. This is one of those times. Once we begin to understand all the stories at play, we can begin to see which one we are taking part in, and what choices we must make.

Winter is here in the north. Tomorrow is the solstice. In the west of Ireland it is dark, damp and cold. The times are raging around us, and it can be hard to keep our heads. But candles are lit in the windows here at night, for it is advent, and an unexpected light is about to break through the shortest of days. The times demand now that we remember and cultivate some of the old virtues. We could start with courage: courage and patience. It may take years, decades, centuries, but the Machine we have built to manage life itself, to squeeze the world into our own small shape – it will come down in the end, and the humming wires will fall silent. Our task in the meantime is to understand, so that we can resist, the shape of the tyranny it brings. But D. H. Lawrence knew: all the prophets knew. The Earth cannot be reset. Not by us; not ever.

They talk of the triumph of the machine,

but the machine will never triumph.Out of the thousands and thousands of centuries of man

the unrolling of ferns, white tongues of the acanthus lapping at the sun,

for one sad century

machines have triumphed, rolled us hither and thither,

shaking the lark’s nest till the eggs have broken.Shaken the marshes, till the geese have gone

and the wild swans flown away singing the swan-song at us.Hard, hard on the earth the machines are rolling,

but through some hearts they will never roll.