Written by William Rivers Pitt / Truthout

Friday, August 2, marked the 29th anniversary of Operation Desert Shield, the military action that heralded the onset of the Gulf War in Iraq. That conflict, shifting from one iteration to the next, never ended.

Desert Shield became Desert Storm, which then became a long, violent police action under the Clinton administration. During that period, sanctions against Iraq were responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of children. Smaller punitive attacks augmented the body count during this time. When confronted with these figures, then-U.N. Ambassador Madeleine Albright said, “The price was worth it.”

After the “election” of George W. Bush and the subsequent terrorist attacks of September 11, the Iraq War entered a new and far more violent stage. The 2003 re-invasion of Iraq, undertaken with a much smaller international coalition and buoyed by brazen lies from U.S. and British intelligence, killed, maimed and displaced millions of civilians.

At almost the same time as active combat was reinitiated in Iraq, the U.S. opened a parallel front in what became known as the war on terror, this time in Afghanistan. In the 17 years since our conflict in that country began, hundreds of thousands of civilians have also been killed or displaced, and thousands of U.S. and coalition troops have been killed or wounded.

The dying has not ended in Iraq or Afghanistan.

“At least two Iraqi people were killed and 20 others injured in a suicide bombing near a Shiite mosque in southwestern Baghdad,” Iraqi Newsreported on July 15. “Violence in the country has surged further with the emergence of Islamic State extremist militants who proclaimed an ‘Islamic Caliphate’ in Iraq and Syria in 2014.”

The violence in Afghanistan, too, is ongoing. “Last year was the deadliest year for civilians during the entirety of the Afghan conflict,” reports The Washington Post, “with 3,804 civilian deaths and 7,000 wounded.” On Monday, two U.S. soldiers were killed in Urozgan province, bringing the total number of U.S. troops killed in Afghanistan this year to 14.

“The number of civilians injured or killed in US air strikes in Afghanistan has almost tripled in the first six months of this year compared to the same period last year, according to the UN,” reports The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. “Among the civilian casualties recorded by [The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan] so far this year are ten children, all members of the same family, who were killed with at least three others in a US strike in Kunduz.”

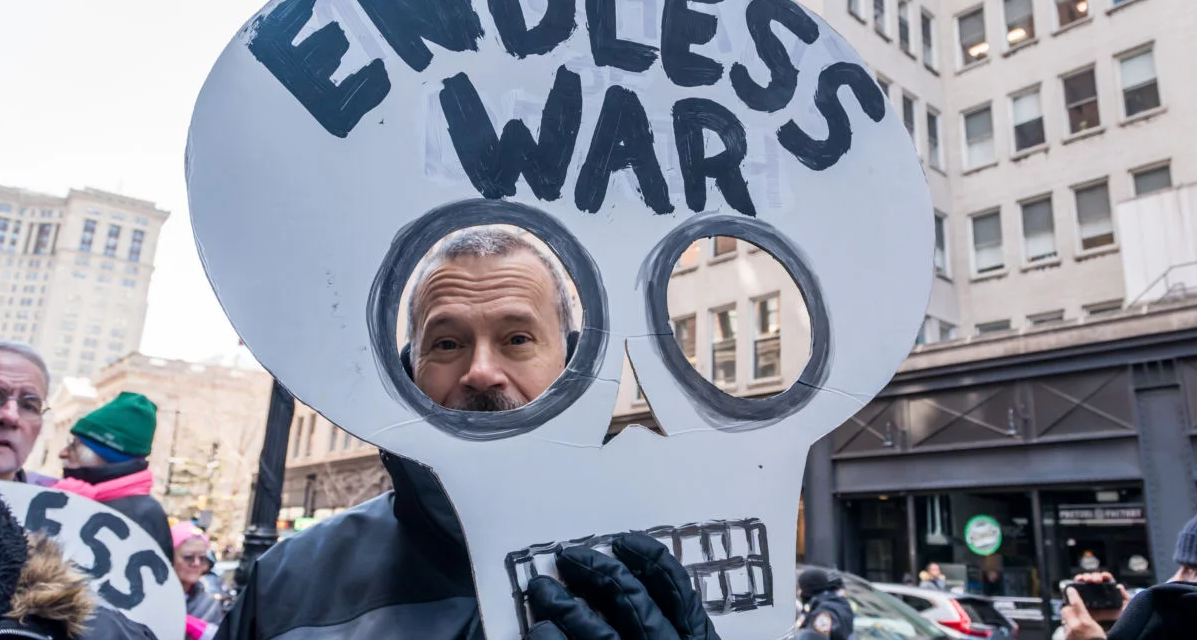

The ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have become the Forever War, and it is not the first of its kind.

U.S. involvement in Vietnam began in 1947, when President Harry Truman announced his government would aid any nation threatened by communism. President Dwight Eisenhower introduced the “domino theory” of communist aggression in Southeast Asia in 1954, and the first U.S. soldiers were killed near Saigon in 1959.

The U.S. war in Vietnam ground on for another 16 years, culminating in defeat with the fall of Saigon in 1975. More than 58,000 U.S. troops were killed in that war, along with millions of Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian civilians.

The Gulf War anniversary put me in mind of a note I received from a Vietnam veteran. The veteran, Dennis, shared his story with me because I have written several articles over the years about the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) endured by U.S. servicemembers returning from multiple deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan. He reached out so that others might know his pain.

Dennis was returning home one perfectly ordinary day when he found himself at a stoplight by the headquarters to a large software company. “As I waited for the light to change,” he wrote, “I first sensed more than heard the beating of a chopper’s blades.” As a corporate helicopter flew overhead and descended into the software company compound, Dennis felt himself coming very suddenly undone.

“As the beating of the blades became louder and more distinct,” he wrote, “I could feel the panic rising and could almost envision the adrenaline my body was releasing into my bloodstream. Images of exploding shells and falling men began to strobe across my windshield to the point I almost lost sight of the road.”

After many long minutes of tears, shuddering and fear, along with a pill to calm his body, Dennis was able to get himself home. He was in a state of almost complete disorder for the remainder of the day, terrified, senses elevated into full fight-or-flight mode. The medicine, which he always keeps with him for such moments, only took the leading edge off a trauma that had mugged him once again.

“My PTSD is mild compared to many,” Dennis wrote. “But it is real. The pain is real and the chokehold it puts on the lives of those afflicted with it oftentimes makes it virtually impossible to even try to live some semblance of a normal life.”

So it is today with veterans of the Forever War. Suicide has spiked among U.S. soldiers returning from multiple deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, and the Veterans Administration has struggled to contend with “the approximately 20 suicide deaths every day among veterans” according to The New York Times. “Veteran suicide is something that’s been an incredible thing to watch,” said Donald Trump on March 5. “Hard to believe.”

Not hard at all, Mr. President, and hardly incredible. War is hell for all who endure it.

Studies of PTSD among soldiers returning from war have been well documented, even as the physical and emotional effects of prolonged exposure to war remain poorly understood by the public. Particularly for civilians affected by the traumas of war, the available data remains sparse. What is available, however, is profoundly disturbing.

“Based on the slim available evidence base, the global number of adult war survivors suffering PTSD and/or MD [major depression] is vast,” the European Journal of Psychotraumatology reported in November 2018. “We estimate that about 1.45 billion individuals worldwide have experienced war between 1989 and 2015 and were still alive in 2015, including one billion adults. On the basis of our meta-analysis, we estimate that about 354 million adult war survivors suffer from PTSD and/or MD. Of these, about 117 million suffer from comorbid PTSD and MD. Most war survivors live in low-to-middle income countries with limited means to handle the enormous mental health burden.”

I received another note just this week from a veteran who returned from the beginning of the Iraq War more than 20 years ago to become a fierce advocate for his fellow veterans. This soldier, who asked that he remain anonymous, had a simple message: “Please, for the love of God, do anything you can to add your voice to those who oppose sending our troops into the fiery hell of war. If we are to survive as a nation, we must become a nation of peace, not the war machine we now are.”

The lessons of Vietnam and its aftermath were not heeded, and another full generation continues to pay the price.