Written by Dave Holmes / LINKS

October 11, 2019 — Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal — The current climate crisis — global warming — is the greatest threat ever faced by humanity. The survival of the human race is at stake. The reality of the heating of the planet can’t rationally be denied.

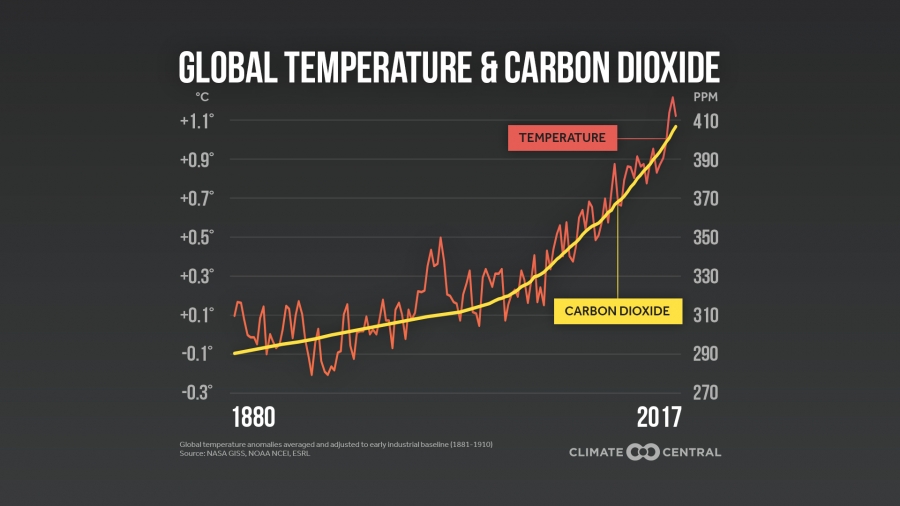

CO2 emissions continue to rise. The atmospheric concentration of CO2 is now north of 410 ppm. This is the highest level in 800,000 years. The planet is clearly getting hotter. There are now more extreme weather events — more devastating floods, more debilitating droughts, more catastrophic hurricanes and tornadoes, more searing heatwaves, more destructive storm water surges in coastal areas. We can expect to cross some key tipping points very soon, ushering in a world very different to anything we have ever known.

The burden of these events falls most heavily on poor people and especially on Third World countries where the infrastructure is much weaker.

Climate emergency

In their 2008 book Climate Code Red, David Spratt and Phillip Sutton raised the idea of a climate emergency, something which necessitates society going beyond a business-as-usual approach and recognising the existential nature of the crisis.

Recently the UK parliament voted to declare a climate emergency, following declarations by the Welsh assembly and the Scottish National Party leader Nicola Sturgeon. These declarations followed the first global student strikes and the Extinction Rebellion protests.

However, important as declaring a climate emergency is, a mere declaration is not enough. The key question is what should be its political and economic content? What do we want to see happen?

Limits of World War II analogy

Climate Code Red cites the United States in World War II as an example of an emergency transformation of the economy.

Faced with a crisis situation the US government and big business carried out a dramatic switch of production from civilian needs to war material. Within months production lines went from producing washing machines or cars to producing submachine guns and tanks (see photo above). Military production went from 2% of GDP in 1941 to 40% in 1943. Stringent rationing was introduced in whole number of areas (rubber, petrol, food, clothing, etc).

There was a similar mobilisation of resources in Australia.

This example shows what can be done when there is a will. However, it is important to note the political-economic context in World War II: If the Axis powers had been victorious, US capitalism would have been finished. For the US capitalist class this was a struggle for survival — and world domination.

All military contracts were made on a cost-plus basis so there was no risk. The new plants were either paid for by the government, depreciated very quickly and/or given big tax breaks. Being “the arsenal of democracy” (as they called it) was a huge profit bonanza for US big business.

Today we need to carry out a transformation of the economy but while we need more houses and suchlike, we don’t need more consumerist “stuff” — in fact, we need to move away from it big time. We need an economy that is sustainable, decarbonised and with as little waste as possible and focused on meeting people’s needs. The capitalists are not interested in this.

Capitalism is the problem

The climate crisis is not due to you and me — we may be forced to drive a car, use overpackaged products or use energy-guzzling air-conditioners to heat or cool our poorly insulated homes. Ordinary people have no real choice. Rather, the climate crisis flows from the insatiable drive of corporate capitalism for profits. Its only imperative is maximising profit — all the rest is simply window dressing.

In its drive for profit capitalism “externalises” a whole series of costs, i.e., doesn’t acknowledge them, let alone pay for them, but passes them on to society which has to bear the burden. Thus the capitalist economy produces planet-warming greenhouse gases, pollution of all kinds and prodigious amounts of waste — in the production process itself, by producing products designed to wear out quickly and that can’t be recycled, and wrapping them in insane amounts of packaging. And, perhaps most importantly, it treats nature as an inexhaustible source of raw materials and as a bottomless toilet for waste.

(Walking the streets of my suburb of Brunswick in Melbourne just before a hard rubbish collection day gives you a depressing idea of where so much stuff ends up when it is no longer wanted. It’s piled up on the nature strips: microwaves, chipboard furniture, plastic frames and all the other junk. The corporations sell us this stuff but take no responsibility for what happens to it when its useful life is over.)

Capitalism or a habitable planet

Left-wing writer and comedian Robert Newman put it very well in a 2006 Guardian article:

Our economic system is unsustainable by its very nature. The only response to climate chaos and peak oil is major social change . . .

There is no meaningful response to climate change without massive social change. A cap on this and a quota on the other won’t do it. Tinker at the edges as we may, we cannot sustain earth’s life-support systems within the present economic system.

Capitalism is not sustainable by its very nature. It is predicated on infinitely expanding markets, faster consumption and bigger production in a finite planet . . .

You can either have capitalism or a habitable planet. One or the other, not both.[1]

Can capitalism go green?

Some people in the climate movement argue or assume that capitalism can go green. I think that is simply wishful thinking and flies in the face of reality.

Even if they happen, any positive changes made will be too slow, too late, too half-hearted and undermined by accommodations to huge vested interests. Capitalism has invested tens of trillions dollars in the fossil fuel economy. It can’t and won’t just write these off.

Look at the current hype around electric vehicles. OK, EV are better than petrol or diesel vehicles. But beyond the power source is the issue of the commodification of transport. In my opinion, a city full of millions of EV would still be disaster — we would still have some 40% of the land area given over to roads, parking and service facilities. We need renewable energy, massive investment in public transport and individual car use pushed to the margins. This would enable cities to be redesigned in forms more suitable for human beings and community life.

And when it comes to producing what is actually needed and ceasing to produce the current unsustainable consumerist torrent of “stuff”, capitalism is just not interested. Selling stuff is what it is all about.

Yes, we should push for stringent regulations and better recycling but you can only go so far trying to control something that is intrinsically antisocial. Furthermore, recycling has its limits. We need to switch to a completely different economic model based on eliminating the waste at the point of production and producing for people’s real needs.

Public ownership & planning

Comprehensive, society-wide planning is absolutely vital if we are to grapple with the crisis of climate change. This planning must be democratic, directly involving communities. And to plan we need direct control of the economy. Capitalism lacks control. It uses indirect levers and everything is refracted through the greed of private capitalist interests.

The key thing we need is a massive expansion of public ownership, whether federal, state or municipal. In particular, the banking and financial sector, which is at the heart of our economy, needs to be nationalised. The power and energy sector also needs to be in public hands so we can make the big switch to maximum sustainability as rapidly as possible.

The “commanding heights” of the economy need to be in the hands of society. And I would stress that these assets need to be not only publicly owned but democratically controlled by the people — with workplace democracy, no huge inflated managerial salaries, and forms of real public control and accountability.

Naturally, the bosses and their ideologues will scream that nationalisation is immoral and impossible, that it doesn’t work and so on and so on.

The late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez put it very well: Private property is not an absolute right, he said. The needs of the community must come first. We are not talking about people’s homes or small businesses but the big means of production, distribution and exchange on which society’s welfare depends.

Politically, we need a climate action government — a radical, anti-austerity, anti-capitalist government based on the mobilisation of huge masses of people — to carry through the necessary transformations.

Who bears the cost? A ‘just transition’

Dealing with climate change will necessitate vast economic transformations. We will stop producing some things and have to produce more of others, and we will have to start producing everything in a different way.

A basic principle should surely be that ordinary people should not have to bear the cost of this transition. It has to be as equitable and democratic as possible.

But capitalism is incapable of any real sort of “just transition”. Look at what happened when Morwell’s coal-fired Hazelwood power station closed down in March 2017. Some 450 workers and 300 contractors lost their jobs. The government provided some funds for “retraining” but whether laid-off workers found jobs in the area was basically up to them and whether the private companies were hiring. Many workers have had to move interstate for work. Many of the local jobs available are poorly paid.[2]

The only way around this depressing result is planning based on public ownership and projects to meet community needs — houses, schools, hospitals and healthcare, public transport, sustainable agriculture and so on.

Climate change ‘locked in’

Even in the utterly fantastic eventuality that climate virtue descended immediately over the entire planet — that is, we decarbonised our economy — drastic climate change would still be “locked in”.

Already the US uber rich have had private seminars on how to survive in the face of the catastrophe and the expected breakdown of social order. Some are buying islands or acquiring property in New Zealand. They have some truly thorny questions to ponder: For instance, if you get away to your secure retreat by helicopter or plane, do you have to include the pilot’s family as well?[3]

The illustration above shows the guarded entrance to an old missile silo in the US housing a number of luxury apartments where rich owners can hole up for a long time when the apocalypse comes.

Elon Musk is pondering a move to Mars. Jeff Bezos is talking about moving production to the Moon although I don’t think he has solved the problem of how to get all the stuff back to Earth.

The completely individualist “solutions” favoured by many of the capitalist oligarchy aren’t an option for the majority of us. The only solution for ordinary people is collective action to try to change things at source and to try to protect people.

Climate action has to include people protection measures and these will have to be profound and on a truly unprecedented scale. There is simply no way that capitalism is going to consider these. If we continue with capitalism into the climate change inferno, the rich will try to save themselves and the mass of people will be condemned to a hellish existence. It will be like Soylent Green or Bladerunner but even worse. Most of us will perish.

New Orleans & Hurricane Katrina

The 2005 devastation of New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina shows us how climate change will impact us if it’s left to capitalism.

More than one million people fled the city. Hundreds of thousands never returned.

New Orleans city officials decreed that people who had not started to rebuild their homes after a year would have their property taken from them. Hundreds of properties were confiscated, resulting in a change in the class and ethnic composition of previously poor Black areas, and a sharp decline in their overall population. In other words, Black communities have been broken up and much of their population moved out. Nearly 1 in 3 Black residents have not returned to the city after the storm.[4]

Tens of thousands of the poorest never fled the city because they had no means of fleeing and no place to flee to.

Just compare this to what happens in neighbouring Cuba. There hurricanes cause a lot of infrastructure and agriculture damage but very small loss of life due to the comprehensive mobilisation of resources that swings into place when disaster threatens — there are emergency workers, volunteers, community shelters and a well-rehearsed plan.

People protection measures vital

The photo above shows a homeless man in Phoenix sheltering during a heatwave in 2017.[5]

Under the heading of people protection we can identify a number of issues. Just to list them is to realise that the capitalist system is not going to address them in a remotely adequate way.

Protection from heat. Not only do all new buildings and dwellings need to be properly insulated to cope with the seriously rising temperatures, but millions of existing dwellings need to be retrofitted. This needs to be a national mobilisation led by governments, overriding private interests (landlords and developers). People need to be able to keep cool and avoid ruinous power usage.

For example, if landlords refuse to carry out the changes, confiscate their properties and take them into the stock of the government housing authority.

Look at the fiasco over flammable cladding. That tens of thousands of buildings around Australia were allowed to be clad with the equivalent of petrol-soaked rags beggars belief — even for a cynical socialist. But now the authorities seem completely unable to rectify the problem, hopelessly dithering and buck passing to the individual owners who are the victims here.

Do we really believe that these same authorities are going to deal with the home insulation problem which is even bigger?

We need to end the problem of homelessness. Otherwise we’ll have our own Phoenix-type situations here with the poor dying of exposure during heatwaves. The solution is simple. Build tens of thousands of properly insulated, quality public housing units each year, with rents tied to income (say 10-20%). This would also decisively break the grip of speculators on the rental market and drive all rents down.

We need heat refuges — enough of them — funded by governments and with the necessary ancillary staff and facilities. The most vulnerable could be taken there in crisis situations and looked after.

Protection from bushfires. A lot of people live in bushfire-exposed areas in the outer suburbs. The Dandenongs in outer Melbourne, home to 60,000 people, is a prime instance. Telling people to flee is not practical for many (no money, nowhere to go, etc.). There need to be fire refuges. So far Victoria has a mere five although there are other safety zones.

Protect people displaced by climate change. What is going to happen to people who are forced to move by climate change — those who are forced to retreat from the bush and urban fringes, those who are forced to retreat from low-lying areas due to sea-level rise, storm surges and flooding? Are they going to be on their own, at the mercy of the market or will there be a proper plan and resources (especially public housing)?

Protect our water supply. Our water supply needs to be guaranteed. The absolute priority has to be people’s basic needs and our food supply. The Murray-Darling water crisis shows that the governments are completely in hock to agribusiness.

Protect our food supply. The food supply needs to be guaranteed. Agriculture needs to be transformed away from industrial, high input monocropping to small farm intensive eco-agriculture. There will have to be less meat, we will have to be more vegetarian — it is a question of necessity.

We need to grow as much of our food as close as possible, reducing food miles to the minimum. We need to promote urban gardens and local markets on the largest possible scale.

(It has long astounded me that supermarket shelves are flooded with tins of Italian tomatoes. Think about that! Tomatoes in Italy are put in metal tins and shipped around the world to be sold here dirt cheap. I like Italian tomatoes but we have to ask if this is a rational use of our resources.)

Food must be affordable for the poorest. The big capitalist supermarket chains (Coles, Woolworths, Aldi etc.) must be nationalised so that everyone can get good cheap, healthy food. If necessary rationing may have to be introduced (as in World War II). Otherwise we may well end up with $5 tomatoes, $10 cabbages and so on.

Conclusion

Capitalism’s drive for profit at all costs is responsible for the climate crisis. In order to have a hope of halting the damage and coping with what is already locked in — let alone drawing down the CO2 already in the atmosphere — we will have to move beyond capitalism towards a society where the needs of the mass of people come first.

The future is uncertain. Collectively we have to rebel and force through the necessary changes or face extinction. There is no other way.

Notes

- Guardian, February , 2006.

- “Workers’ job heartache”, Latrobe Valley Express, October 29, 2018.

- “Doomsday prep for the super-rich”, The New Yorker, January 22, 2017.

- Phil Hearse, “The Politics of Hurricanes — climate catastrophe victimises the poor”.

- “Burned feet, parched throats: Arizona homeless desperate to escape heatwave”, Guardian, June 24, 2017.

![They Actually Admitted They’re Lying To You! [News + Comedy with Lee Camp]](https://cncl.info/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/they-actually-admitted-they-8217-re-lying-to-you-news-comedy-with-lee-camp-CvXVBDs_fKw-440x264.jpg)