Written by Jo Wills / CNCL Staff Author, New Zealand

The reaction of a community to an infrastructure project is often a good indicator of whether or not it will deliver to their needs. We rely on transport infrastructure to connect us to destinations, people and experiences. The way we move about towns and cities directly impacts our wellbeing. Therefore roads should be designed to enable safety, sustainability, efficiency and choice. When there is no choice other than to own a car, the design is flawed.

Tauranga is a small city on the east coast of the North Island of New Zealand. Because of its location, lifestyle and the obscene housing market in neighbouring larger cities, it’s been the destination of choice for a number of years. As a result, it’s one of the fastest growing cities in the country and it’s grappling with all of the pressures of such. Transport has become a huge issue and the community is bearing the brunt with congestion, pollution and increasing public anger at the problem.

To add to the complexity of rapid expansion, Tauranga has a combination of minor and major roads (state highways) running right through its communities. Freight in the form of logging trucks and refrigerated lorries entering from the East and West to get to the port. The Port of Tauranga proudly boasts being the busiest in New Zealand, this position affording them considerable power.

Tauranga isn’t unique in its growing pains and under the previous New Zealand government, pressure points were identified across the country as hindering productivity with congestion. The answer to this— more and bigger roads.

Under this master plan B2B project was born. The B’s stand for Bayfair, one of the largest shopping centres in Tauranga, and Baypark, the major sports and event arena. Each major destination sits on either side of both a state highway and a railway.

However, for twenty years, children, the elderly, cyclists and pedestrians have been safely and efficiently reaching schools, employment, shopping, medical centres and bus stations without any interaction with the state highway traffic (or railway) via an underpass.

B2B was all about separating freight from community traffic through the construction of a freight overpass, effectively reducing the travel time to port by three minutes. Someone smarter than me calculated the economics of the three-minute reduction and come up with a cost-benefit ratio suitable to justify a $120 million budget to complete the project.

At its core, this project has some benefit. Double train logging trucks rattling through what is essentially the middle of two big communities isn’t ideal. Given the port has growth projections to increase these movements, introducing a freight bypass ticks one of the safety boxes that a good infrastructure project should.

However, in the 2016 B2B design, the child, elderly, pedestrian and cycle-friendly underpass was removed.

In its place came an at-grade series of traffic light controlled pedestrian crossings spanning the newly expanded round about. This would see a child walking to school having to cross up to three roads each with up to three lanes of traffic, stopping at each set of lights. The irony of this, while the project was designed to free up local traffic, the same traffic will now be slowed down by approximately five hundred people per day pressing the button to activate each pedestrian crossing.

The community reacted with understandable distress, frustration and anger. Groups formed and a strong opposition was mobilised. The underpass provided a level of service that enabled active transport and community connection. It was a safe, efficient and effective way to avoid the heavy traffic above. The proposed at-grade crossing did not. Then in 2018, after countless meetings, social media campaigns and pressure, a surprise win. The New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) in charge of the project agreed to reinstate the underpass pending a new budget.

The community reacted with understandable distress, frustration and anger. Groups formed and a strong opposition was mobilised. The underpass provided a level of service that enabled active transport and community connection. It was a safe, efficient and effective way to avoid the heavy traffic above. The proposed at-grade crossing did not. Then in 2018, after countless meetings, social media campaigns and pressure, a surprise win. The New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) in charge of the project agreed to reinstate the underpass pending a new budget.

Cut to July 2019, the cost for the underpass came out at $33 million. This was followed by a quick backtrack by the NZTA and the Transport Minister. It would not be reinstated.

Having been involved in the numerous meetings with those responsible for delivering this project as well as being a user of active transport and the underpass, I’ve drawn a few conclusions.

- Designing transport projects to help free up traffic is a flawed approach if done in isolation or prioritisation to the safe and active movement of people. This results in a prioritisation of vehicles, sending the message, ‘drive your car’, which in turn creates the need for more roads. It’s a vicious cycle that locks in congestion and pollution.

- Costing transport projects based on the economic return externalises any social or environmental impacts (good and bad). The B2B project was budgeted at $120 million and this was deemed a worthwhile investment for freight to reach the port three minutes faster. However, the costs to the community’s physical health and wellbeing of losing the underpass (estimated at billions) and the environmental impact from emissions were not included in the calculations.

- The community needs to participate in the early stage concept designs of any major (local) transport projects. It’s not enough to present a project as a forgone conclusion and then ask for feedback. Had this particular project started out with, ‘What do you value most about moving about in this community?,’ it might have become clear just how vital a role the

underpass plays and the high level of service it delivers.

underpass plays and the high level of service it delivers.

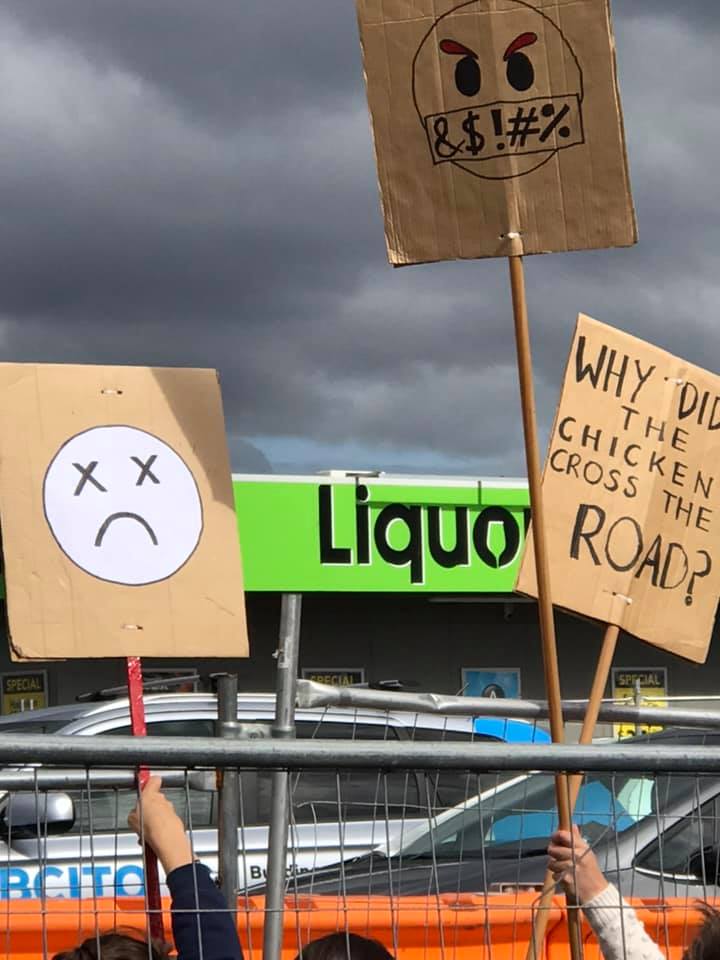

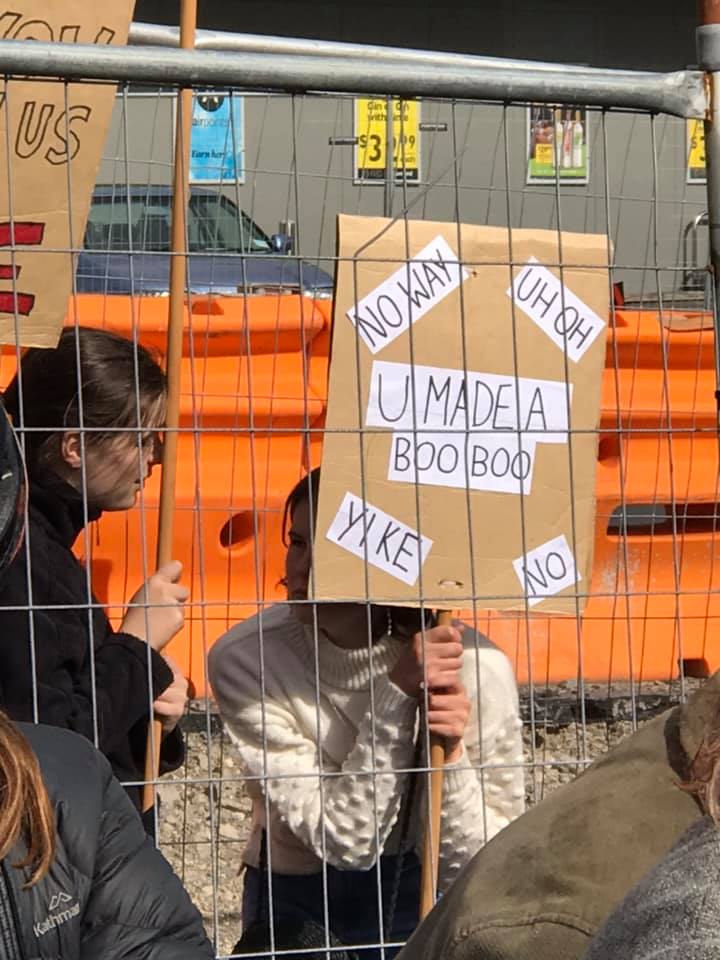

A protest was organised in August to show a unified resistance to the latest decision to remove the underpass. Hundreds of people showed up. The community showed up. Mobility scooters driven by people who use the underpass as part of their daily outing were there, school children terrified at the thought of crossing multiple lanes of traffic came along, parents with prams and cyclists were out in force.

The message to the decision makers was loud and clear: “You have got this wrong!”

But where to from here? The future for this project is yet to be determined but the locals are definitely prepared for a fight. The ultimate decision maker in this instance is the New Zealand government. The same government with a transport policy which prioritises active transport and low emissions. Had the B2B project been reviewed under this policy, chances are it wouldn’t have met the criteria needed to get the green light. Perhaps that’s the simple answer.

Should it go ahead without the underpass, data doesn’t exist of what the impact to the community and environment will be. This is because these impacts weren’t included as part of the project planning. The people who do know are those who use that underpass every day. This where things have gone wrong, the community knows what it stands to lose.

The community does know what’s good for it when it comes to safe, efficient, sustainable transport infrastructure that offers choice; someone just needs to ask us.

The community does know what’s good for it when it comes to safe, efficient, sustainable transport infrastructure that offers choice; someone just needs to ask us.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks