Written by Mongabay.com

- In a comment article published in the Nature last month, scientists argue that an “energy future in which both people and rivers thrive” is possible with better planning.

- The hydropower development projects now underway threaten the world’s last free-flowing rivers, posing severe threats to local human communities and the species that call rivers home. A recent study found that just one-third of the world’s 242 largest rivers remain free-flowing.

- The benefits of better planning to meet increasing energy demands could be huge: A report released by WWF and The Nature Conservancy ahead of the World Hydropower Congress, held in Paris last month, finds that accelerating the deployment of non-hydropower renewable energy could prevent the fragmentation of nearly 165,000 kilometers (more than 102,500 miles) of river channels.

In a comment article published in the Nature last month, scientists argue that an “energy future in which both people and rivers thrive” is possible with better planning.

For decades, hydropower dams have been a go-to solution for electrifying the developing world. There are more than 60,000 large dams around the globe, and as the demand for clean energy in Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia continues to grow, hundreds more are currently in the planning stages.

Hydroelectric dams have their advantages, such as providing a steady supply of baseload electricity that can be adjusted quickly to meet fluctuating demand and zero hazardous wastes or byproducts to dispose of. But according to the authors of the Nature article, led by Rafael J. P. Schmitt at Stanford University, “Hydropower needs to be viewed as part of a broader strategy for clean energy, in which the costs and benefits of different sources should be assessed and weighed against each other.”

The hydropower development projects now underway threaten the world’s last free-flowing rivers, posing severe threats to local human communities and the species that call rivers home. The Cambodian government, for instance, is proposing to build the 11,000-gigawatt-hour Sambor dam on the Mekong River, which “would prevent fish from migrating, threatening fisheries worth billions of dollars. It would further cut the supply of sediment to the Mekong Delta, where some of the region’s most fertile farmland is at risk of sinking below sea level by the end of the century,” according to Schmitt and colleagues. “And the dam would do little to bring electricity or jobs to local villagers: much of its hydropower would be exported to big cities in neighbouring nations, far from the rivers that will be affected.”

A recent study found that just one-third of the world’s 242 largest rivers remain free-flowing, mostly in remote regions of the Amazon Basin, the Arctic, and the Congo Basin.

As Schmitt and co-authors note in the Nature article, however, hydropower is just one of many clean energy options available today, and technologies like solar panels or wind turbines can produce similar amounts of electricity as large hydroelectric dams at roughly the same cost.

“[S]preading a variety of renewable energy sources strategically across river basins could produce power reliably and cheaply while protecting these crucial rivers and their local communities,” the researchers write. “Solar, wind, microhydro and energy-storage technologies have caught up with large hydropower in price and effectiveness. Hundreds of small generators woven into a ‘smart grid’ (which automatically responds to changes in supply and demand) can outcompete a big dam.”

Schmitt and team say that, in order to keep the world’s remaining free-flowing rivers unobstructed while increasing access to electricity in developing nations at the same time, strategies for deploying renewable energy technologies and expanding hydropower projects must be made at the basin-wide or regional level and strike the right balance between impacts and benefits of all available clean electricity generation methods. “On the major tributaries of the lower Mekong, for example, dams have been built ad hoc. Existing ones exploit only 50% of the tributaries’ potential hydropower yet prevent 90% of their sand load from reaching the delta,” the researchers report. “There was a better alternative: placing more small dams higher up the rivers could have released 70% of the power while trapping only 20% of the sand.”

Site selection for solar and wind farms must be just as strategic as for new dams. “Impacts of these projects on the landscape need to be considered, too. Solar and wind farms might be built on patches of land that have low conservation value, such as along roads, or even floating on hydropower reservoirs,” Schmitt and co-authors suggest. “Solar panels and small wind turbines can be put on or near buildings to minimize infrastructure and reduce energy losses in transmission.”

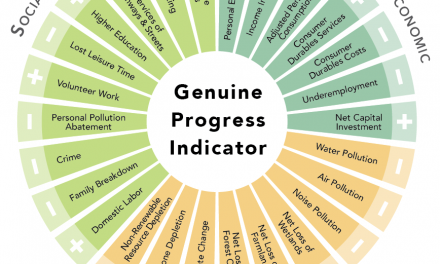

The scientists recommend that organizations and governments who manage river basins apply a “holistic perspective” to energy planning that takes into account all non-hydropower renewable energy options, energy efficiency measures, energy demand management, and the risks posed by global climate change — as decreasing river flows in a more drought-prone, warmer world could severely impact the output of hydroelectric dams.

But in order to properly evaluate all of the trade-offs when designing a renewable energy strategy, we need to know much more about river ecosystems and the human communities that depend on them: “Researchers need to fill data gaps across whole river basins, from fish migration and sediment transport to community empowerment and impacts on food systems,” Schmitt and co-authors write. “The costs of lost ecosystem services over the life cycle of energy projects must be included in cost–benefit analyses. Such research is cheap compared with the costs of building dams and mitigating environmental impacts.”

The benefits of better planning to meet increasing energy demands could be huge: A report released by WWF and The Nature Conservancy ahead of the World Hydropower Congress, held in Paris last month, finds that accelerating the deployment of non-hydropower renewable energy could prevent the fragmentation of nearly 165,000 kilometers (more than 102,500 miles) of river channels.

“We can not only envision a future where electricity systems are accessible, affordable and powering economies with a mix of renewable energy, we can now build that future,” Jeff Opperman, a freshwater scientist with WWF and lead author of the report, said in a statement.

“If we do not rapidly seize the opportunity to accelerate the renewable revolution, unnecessary, high-impact hydropower dams could still be built on iconic rivers such as the Mekong, Irrawaddy, and Amazon — and dozens or hundreds of others around the world. It would be a great tragedy if the full social and environmental benefits of the renewable revolution arrived just a few years too late to safeguard the world’s great rivers and all the diverse benefits they provide to people and nature.”

CITATIONS

• Grill et al. (2019). Mapping the world’s free-flowing rivers. Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1111-9

• Opperman, J., J. Hartmann, M. Lambrides, J.P. Carvallo, E. Chapin, S. Baruch-Mordo, B. Eyler, M. Goichot, J. Harou, J. Hepp, D. Kammen, J. Kiesecker, A. Newsock, R. Schmitt, M. Thieme, A. Wang, and C. Weber. (2019). Connected and flowing: a renewable future for rivers, climate and people. WWF and The Nature Conservancy, Washington, DC.

• Schmitt, R. J., Kittner, N., Kondolf, G. M., & Kammen, D. M. (2019). Deploy diverse renewables to save tropical rivers. Nature 569, 330-332. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-01498-8