Written by Jo Wills / CNCL staff writer, New Zealand

What’s the measure of success of good urban form? For me, it’s equity. This looks like all members of the community enjoying access to safe, reliable and affordable transport that connects them within the community and to amenities. It’s housing that doesn’t have labels like ‘social’ and ‘affordable’ – everyone gets to live in a space that benefits their wellbeing. It’s also when the intrinsic value of nature is incorporated into our spaces, not built out.

Stakeholders in the Western Bay of Plenty, New Zealand, are being asked to describe their long term views as part of the Urban Form and Transport Initiative or UFTI for a catchy abbreviation. This piece of work will consolidate all past pieces of work focused on transport and urban planning previously completed and deliver one master plan to solve all of the problems which come with being a fast growing region.

This is a good thing on the surface; however, perspective is everything.

Growth under the traditional linear model that governs our economy is considered a good thing. As long as GDP increases, we slap each other on the backs and say job well done. The impacts of this, such as congestion, pollution, loss of productive land, loss of conservation land and biodiversity as well as increasing poverty, are nuisances but accepted as part of a successful economy. That is until these impacts start to hinder the ability to keep growing. This is where we have found ourselves.

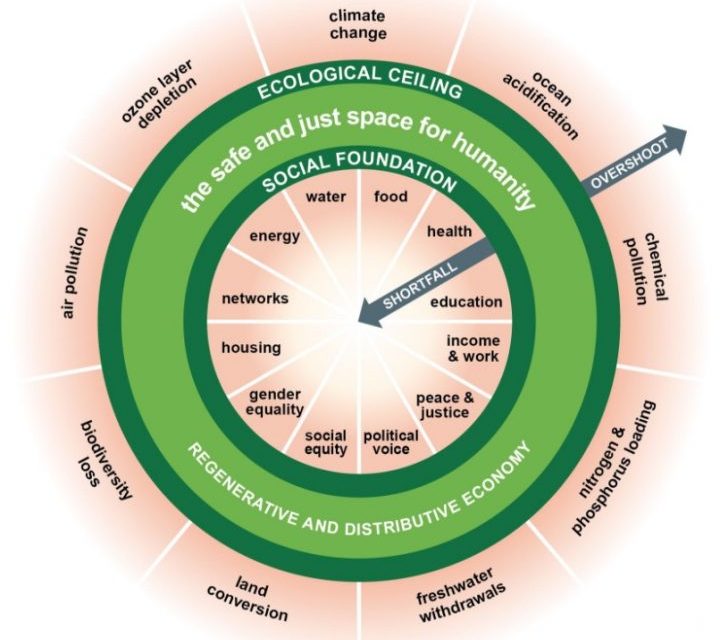

In a different model, unrestrained growth is not considered a good thing. For more information about this, Kate Raworth provides an alternative model she calls the Doughnut. This puts meeting the needs of all at the centre of the model but the difference is, doing so stays within the planetary boundaries. It provides another way to understand growth and to measure success.

The UFTI project still recognises unrestrained growth as a good thing, although it hints at this maybe no longer being a smart thing. It presents the pressures in economic terms which set the parameters to simple equations of supply and demand – more land for more houses and more roads for more cars.

This approach keeps everything on a “business as usual” track. It keeps investors happy, they get more land to develop. It keeps politicians happy, they get to cut ribbons at the opening of new shopping malls. It keeps business people happy, they get to move more product and grow profit. The GDP will continue to rise, the environmental and social causalities accepted as the cost of growth.

But there is another way.

Imagine what could happen if we changed the parameters to social equity and environmental restoration and preservation, and everything we did was required to meet those needs. If we break that down to basic inputs and outputs, it goes from sounding idealistic to incredibly logical, even possible.

What are the two things an economy needs to prosper? Healthy, skilled, resilient people and an abundance of natural resources. This relationship goes even deeper because people rely on the life giving services nature provides. It’s symbiotic. This is economics 101, not some new age hippy shit.

So what does this look like in terms of a transport system and new urban form for a part of the country bursting at the seams because of population growth? It looks like a shift in the dynamics that have historically determined city and infrastructure development. It puts meeting the needs of all people in the centre and places the measuring stick in there with them.

In her book ‘My Life on the Road’, Gloria Steinem writes that when Ghandi realised that the movement of the people against discrimination lacked roots in the villages, he moved to the villages. This was where ordinary people went about their daily lives vulnerable to the effects of actions not attuned to their needs. Gloria writes, “He began to live like a villager himself…and to measure success by changes in the lives of the poorest and least powerful, village women”.

I experienced a revelation a while ago after reading an article about the way many of our towns and transport systems are designed by men, for men. Not with malicious intent, but without an understanding of how women, children or elderly might need to use a public transport system, or move through a city. A commonality between the above groups is their needs are often under-represented.

For instance, there are many parts of a city or neighbourhood women won’t go at night even if it’s the quickest route home. Think unlit alleyways and stairwells, parks or bus stops isolated from the shops or the movement of people. One of the things a woman might subconsciously weigh up when travelling alone at night might be, “If I have to scream, will anyone be able to hear me.”

Older people who lose their mobility and independence can really struggle with complicated bus timetables and changing buses. This coupled with the placement of retirement villages often on the outskirts of town, not within walking distance to any social space, supermarket or local shops, can mean isolation.

These are issues everyday people can face even if income isn’t a pressure. When it is, the tables turn again and housing can contribute another layer of inequity.

Our homes should keep us safe and well and at the most basic level, be functional. For many low income people, our houses don’t tick any of these boxes. They are cold, damp places of stress because of it. Not only that, low income housing and often social housing is located away from amenities so without a car, there is limited possibility of employment or even engagement with the community.

These are some examples of our current pressures. Good urban form and a fit for purpose transport system would improve the lives of many because needs for health, connection, community, employment and safety would be at the centre of the model. If these pressures could be eased, more people would be able to hold down jobs and ironically contribute back into the GDP (if that’s what we are still working towards).

There is some exciting movement in this direction worldwide. Coming from an angle of reducing carbon emissions, a De-Growth Model is being explored by Scotland. Street Fight – Handbook for an Urban Revolution by Janette Sadik-Khan is a fascinating read about how as the Transport Commissioner for New York, against much opposition, reclaimed the streets for people. And Strong Towns is a movement committed to making towns financially strong and resilient.

The time has come for change in the way we shape our cities and the impact they have on environmental sustainability and social equity. Everything is connected and we can no longer look at the economy and growth in isolation to well-being and sustainability. The challenge to each of us is to accept and embrace the changes coming to our city-scapes and our lifestyles, so we can all be better off.